Financial Planning Blog

Measuring inflation is a dauntingly complex task, as we saw in Part 2. But with Social Security benefits, pension payments, tax brackets, investment and insurance products, not to mention a host of labor and other contracts all linked to an "official" inflation rate, it is a measurement that impacts everyone's pocketbook. One can't help seeing a parallel with a similar statistical mystery--the Bowl Championship Series. Football fans in Idaho are well acquainted with that politically deceitful, statistically convoluted black box that can be counted on each year to send Boise State to the Little Sisters of the Poor Bowl while schools with proper pedigrees divide the financial spoils of the BCS. (See this video on What If Everything Worked Like the BCS--The Spelling Bee.)

We know the BCS is complicated. We know the BCS is crooked. We've almost learned to live with that. But, could it possibly be that measuring inflation is even more complicated than the BCS...and just as crooked?

"There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics." - Mark Twain (attributed to Benjamin Disraeli)

Unless you are into anti-government conspiracy theories--after all this is Idaho, and we do love to hate the Feds--you may never have given much thought to the possibility that the official inflation numbers published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) have been manipulated to your detriment. Over the last few decades the BLS has made important changes to how it calculates the CPI that significantly lower the reported inflation numbers. This is no secret, and the methodology and impact of these changes is well documented. There is considerable controversy, however, as to whether these changes were appropriate, or part of a complex plot to lower the official CPI estimates to order to minimize inflation's apparent impact. And, more importantly, minimize the on-going increases of government expenditures linked to the CPI.

First, a quick summary of the controversial changes in CPI measurement:

- In 1983 the way the changes to cost of owner-occupied housing is measured was significantly modified. A new measurement called owner's equivalent of rent (OER) was substituted for the change in actual housing prices. OER measures the amount a homeowner would have to pay to rent their home, or alternatively would earn by renting their house out in a competitive market. The reasoning behind using OER instead of house prices is that owner-occupied housing consists of both a consumption element and an investment element, and the CPI is designed to exclude investments (e.g. stocks, bonds, real estate.) This is certainly reasonable when you consider that contrary to other price increases, homeowners are usually very happy when the values of their homes rise. There is no arguing that using OER instead of house price changes has resulted in a much more stable index. For example, since 2000 housing prices changes as measured by the Case-Shiller Index have swung wildly between +20% and -20% per year, while OER has moved in a narrow range between 2% and 5%.

- In 1999 the BLS began using a geometric mean formula in the calculation of the CPI. This methodology seeks to reflect consumer substitution behavior, where people make trade-offs on the basis of both price and personal preferences in an effort to maximize their standard of living. Critics claim that if the price of filet mignon goes up, and consumers switch to hamburger, the BLS simply substitutes hamburger for steak and calls it even. The BLS adamantly denies this type of substitution is made, and makes a very reasonable defense. (For an understandable, but lengthy explanation of these changes and other see this 2008 BLS article--Addressing Misconceptions about the Consumer Price Index.)

- Starting in 1998 and phased in over time are hedonic (derived from the Greek word for pleasure) statistical models that adjust for quality changes. Using multiple regression analysis the value of new features or quality changes is estimated by comparing the prices of items with and without that feature. Basically, the BLS is trying to estimate what portion of a price increase (or decrease) is due to quality changes, and whether the consumer is left better or worse off. (Again, see the BLS article for a good explanation.)

On one side of the inflation controversy are economists that contend that the CPI for years was systematically overstating price levels to the tune of 0.8% to 1.6% per year. These were the findings of the Boskin Commission, appointed by the Senate Finance Committee in 1995 to study the effectiveness of the CPI estimates, finally resulting in the late 90's changes mentioned above.

In the other camp are those that believe the pre-1982 methods of measuring inflation would give a truer picture of the debasing of the dollar and the impact of price changes on people's well-being. A well known, vocal proponent of this point of view is Walter J. "John" Williams and his work can be found on his Shadow Government Statistics website. Here is his 2006 take on the changes to CPI measurement:

The CPI was designed to help businesses, individuals and the government adjust their financial planning and considerations for the impact of inflation. The CPI worked reasonably well for those purposes into the early-1980s. In recent decades, however, the reporting system increasingly succumbed to pressures from miscreant politicians, who were and are intent upon stealing income from social security recipients, without ever taking the issue of reduced entitlement payments before the public or Congress for approval.

In particular, changes made in CPI methodology during the Clinton Administration understated inflation significantly, and, through a cumulative effect with earlier changes that began in the late-Carter and early Reagan Administrations have reduced current social security payments by roughly half from where they would have been otherwise. That means Social Security checks today would be about double had the various changes not been made. In like manner, anyone involved in commerce, who relies on receiving payments adjusted for the CPI, has been similarly damaged. On the other side, if you are making payments based on the CPI (i.e., the federal government), you are making out like a bandit.

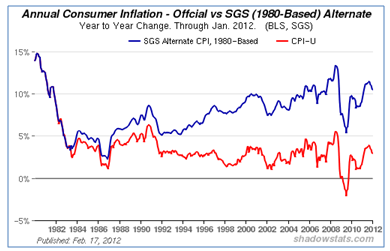

According to Shadow Stats, the current annualized inflation rate, measured using older pre-1982 methodology is about 10.5%, compared to the official rate of a little over 2.9%--over 7% higher!

Ignoring the 1983 housing change, the cumulative impact of the other methodological changes is less dramatic, but still significantly large enough to be make a major dent in the COLA adjustments to your government check.

Are Williams and other critics right, and the federal government is manipulating statistics to hold the official inflation down? I'm not qualified to pass final judgment on the BLS statisics, but I have to say their methodology seems OK to me. For one thing, if the Shadow Stats' numbers were used and Social Security and government pensions were all about double today's level--does that even pass the smell test? It's not like wages and salaries have been rising at a screaming pace. Does it seem right that Social Security benefits and pensions should be rising at over 10% per year? I don't think so.

Just because inflation used to be calculated one way, doesn't mean that is the way it should be done in perpetuity. Just because cost-of-living increases were calculated in the 70's using the old way, doesn't mean it's a good idea for the new millennium. And, just because college football has always had a corrupt bowl system where elite colleges meet to crown a champion and divide the TV money, doesn't mean that is the way it always has to be.

Like the CPI, we should give economists a chance to redesign the college football post season and bring it into the 21st century. One thing for sure, it would certainly look different than the current BCS. Unfortunately for BSU, however, the championship will likely still require kicking a field goal.

In Part 1, the necessity of thinking clearly about inflation was stressed, along with planning for future inflation rates. (For more on this, also see this recent Morningstar article.) However, as it turns out, just figuring out what the current inflation rate is turns out to be much more complicated than most people realize.

Determining price levels and the rate of inflation is not as simple as measuring other things. For example, when you weigh yourself in the morning you just step on the scale and get a nice digital readout. There are, of course, some similarities between prices and our weight--a lot of short term ups and downs, but generally a small percentage movement up and to the right every year. But, think about it. If you are trying to measure price movements, the first question is the price of what? Each of us spends our money on so many different goods and services over the span of a year, and each of us spends our money different than the next guy. If gasoline goes up 5%, and bread goes down 5%, and milk stays even--what does that say about inflation? What if light beer goes down in price, but microbrews go up 5%? What if cable TV goes up so darn much you drop it altogether, saving $100/month?

In order to get a handle on price changes the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics goes to great effort to construct two major categories of price indexes. The first set, which we will ignore for the purposes of this discussion, are the Producer Price Indexes which measure price changes from the perspective of producers along various points of the supply chain. The second set of indexes is the Consumer Price Index, which measures changes from the perspective of the end-use consumer. This is the most familiar, and has the most impact on most of our everyday lives. A quick scan of this document from the BLS tells you the first thing you need to know about inflation--it is an incredibly complex measurement that must take an army of economists and statisticians to pull together.

- Price data is collected every month from over 4,000 homes and 26,000 retail and service establishments of all kinds, in 87 different urban areas across the United States.

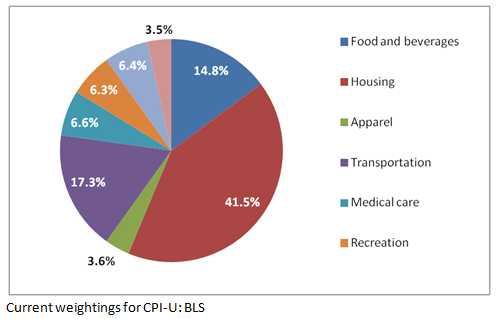

- Prices for goods and services are collected in 8 different major expenditure groups, and these are further divided into about 200 subgroups. Each subgroup has a representative market basket containing hundreds of specific items from specific retail establishments. In all, data on about 80,000 different items is collected in scores of different cities across the country. We're talking soup-to-nuts, mutton to motor oil, frankfurters to floor coverings, from Brockton to Bremerton and Saint Pete to San Fran.

- These representative market baskets were developed from major surveys of thousands of consumers--the last ones back in 2007 and 2008. Detailed diaries and interviews were used to determine the content and relative weighting of the over 200 subgroups. The relative weightings allow the BLS to get compute the index, which is a weighted average of all the items measured. This weighted average may be a good representation of the average consumer, but your individual market basket is undoubtedly very different. The current relative weightings of the eight major expenditure groups are shown below.

But wait, that's not all. You may not have realized there isn't just one CPI number--that would be too simple. There are actually a number of Consumer Price Indexes calculated. These indexes are calculated regionally, then averaged for the country. Also, the indexes are published in both seasonally adjusted and unadjusted form. If you are making any decisions from this data, you want to be careful to understand what you are looking at. Below are the key indexes you likely will see quoted in different contexts.

- CPI-W: The CPI for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers, a collection of households that represent only about 32% of the population. This is an older index with a limited subset of households (wage earners and clerical workers), but is important because it is the one used by the government to adjust Social Security payments on an annual basis.

- CPI-U: The CPI for All Urban Consumers, which covers about 87% of the total US population. This is a superset of the CPI-W, adding many additional categories of workers (e.g. the self employed and professional, managerial, and technical workers), along with the unemployed and retirees. (It is interesting to note that SS payments are adjusted by an index that excludes retirees, the CPI-W. I'm sure this makes sense to someone in the government.)

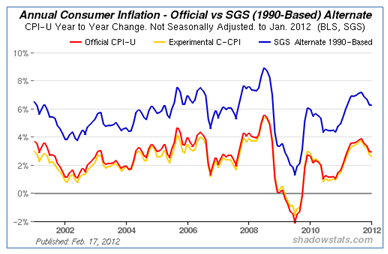

- C-CPI-U: Chained CPI for All Urban Consumers which covers the same set of households as the CPI-U, but uses a different methodology that attempts to reflect substitutions and adjustments consumers make as prices change. There are serious discussions underway to use the C-CPI-U to base adjustments to Social Security benefits, government and military pensions, and tax brackets. The chained CPU approach results in a lower inflation adjustment, and thus would lower government payments over time, along with potentially securing more revenue through slow, stealthy tax increases. (Needless to say, not everyone is a fan of this idea. More on that later.)

- Core CPI: This is an inflation measure that removes the effect of the volatile food and energy components of the CPI. Since food and energy account for close to 25% of the CPI, and often have major short term swings, removing these items results in a major smoothing of the curve, and helps economists observe inflation over the remainder of the economy. The Federal Reserve pays close attention to this number in its role of keeping inflation within desired bounds. The core CPI is often contrasted with the "headline" CPI, or CPI-U. When you hear an inflation number that is totally out-of-sync with what you are experiencing, listen carefully. It is probably the Core CPI that is being quoted.

- CPI-E: This is a CPI measure the attempts to reflect the different "market basket" or spending habits of the elderly. It is an experimental BLS inflation statistic, and you probably haven't heard much about it. However, senior advocates would like the concept to catch on. The argument is that certain categories that older Americans spend more money on, especially healthcare, are underrepresented by the CPI-W. If Social Security was indexed to the CPI-E, cost-of-living increases would, in theory, better represent what seniors experience. And, more importantly, benefits would be presumably higher.

A couple of key points about inflation should be obvious by now. First, it is impossible to get an exact read on what inflation really is. The BLS goes to great effort, and probably does a superb job, but like most statistics about the economy it is an elaborate estimate that takes on the cloak of accuracy. Second, no CPI is going to measure your exact experience with price increases. You experience somewhat different inflation than your next door neighbor (the one drinking light beer while you sip your microbrew), not to mention the retiree in Florida, the oil worker in North Dakota, or the single mother in New Jersey.

What may not be obvious from all of this is the government conspiracy that is currently gaming the inflation numbers. (Yes, this is playing to the local crowd, but the best way to get Idaho readers to continue to the next post is to mention a government conspiracy or complain about the BCS. You get both in Part 3.)

When it is done right, budgeting is really about being very purposeful with your spending. It is best summed up by the John Maxwell quote:

"A budget is telling your money where to go instead of wondering where it went."

In other words: Decide what you are going to do, write it down, do it, and know what you have done. This is the essence of the four fundamental elements of budgeting:

- Prioritizing your needs and wants: Decide what you are (and are not) going to spend your money on.

- Creating and documenting the plan: Write it down and agree on it.

- Executing and living the plan: Do it...figure out how to live according to your plan.

- Tracking your performance: Know what you've spent and how well you are following your plan.

The first two fundamentals have been discussed in previous articles. The final two are where the rubber hits the road and are examined below. There are also more helpful links for those looking to get started on their spending plans.

Executing and living your plan

"A budget tells us what we can't afford, but it doesn't keep us from buying it."-- William Feather

"Your money is like soap. The more you handle it, the less you'll have."--Eugene Fama

Once you have established your spending priorities, you need to live by them. If you are fortunate enough to have sufficient resources to cover most of your wants, this may not be so difficult. For most of us, though, this probably means following through with key decisions like cancelling cable TV, dumping your personal trainer, or selling that F-250 with the hefty payment. These one-time actions may be painful, but once you execute on them they are done and you start reaping the benefits. Often harder is following through on the recurring choices such as not going out to dinner, not buying those shoes, and not going on that unplanned weekend trip. However, if you have bought into a set of overall priorities, you are focused on attainable goals, and you are making shared sacrifices (assuming you have a partner in this endeavor), these behavior changes are achievable.

Key considerations and behaviors:

- Automate as much as possible: Automate your savings toward important goals and setting aside funds for irregular expenses. This can be done quickly and securely with today's on-line savings accounts. You can set up the amount and which day of the month you want money to be automatically moved from your checking account to your on-line savings account. This ensures that these high priority items get funded first. Experts in field of behavioral finance extol the virtues of this kind of automatic savings. David Laibson of Harvard says, "We need to exploit automaticity. We need to build in more of these commitment mechanisms, so we can live up to our intentions."

- Set up separate savings accounts for different goals: On-line banks make creating multiple named savings accounts easy. Consider multiple savings buckets for your emergency fund, new car or major purchase fund, a vacation fund--you name it. Putting a name on every dollar is powerful, especially when the goal is extremely important (e.g. college for your kids), or pleasurable (e.g. that vacation to Hawaii).

- Put aside money for irregular expenses: We all face significant expenses that do not occur on a regular monthly schedule. The effective way to manage these irregular expenses is to put adequate money aside on a monthly basis, in advance. Whether you use a single savings account (or even a cash envelope), or multiple ones (for insurance, clothing, presents, car repairs, etc.), it is up to you. However, if you simply leave this money "unprotected" in your checking account, much of it is likely to disappear and be unavailable when you need it.

- Identify areas for special control: If you are like most people, there are a few areas that are especially difficult for you to stay within budget. Consider using cash and the "envelope system" for those two or three areas that routinely get out of control. Groceries and going out to eat are prime suspects. Or, you might need a Home Depot or movie envelope. The point is, when the money is gone, you get immediate feedback and stop spending. People talk about some of the creative meals they've had after the grocery envelope got emptied.

- Will power may not be enough: If living according to a spending plan was easy, more people would be doing it. Besides the encouragement and teamwork of a spouse, you will likely benefit from the support and accountability of a like-minded community. Find others on the same journey, with the same goal of getting their spending under control and making progress in their financial lives. Likewise, you need to be aware of the kind of company that may derail your good intentions, and take appropriate precautions.

Tracking your performance

"Some couples go over their budgets very carefully every month; others just go over them."--Sally Poplin

"The person who doesn't know where his next dollar is coming from usually doesn't know where his last dollar went."--unknown

In many ways this last fundamental of budgeting should be getting easier for everyone. As more of your spending is moved from cash and check to on-line bill payments and credit and debit card transactions, the flow of our funds should be easier to track, even from your phone. (That is assuming you can still afford that iPhone after you have created your spending plan.)

Key considerations and behaviors:

- Pick a system to track your spending: Although there are many options for tracking your spending, you ultimately have to pick a system you can live with. If you are just starting out, you might want to do some experimentation with different methods to find what works best for you. This doesn't have to be fancy. Many people are still find manually consolidating expense data on an Excel spreadsheet, or with a calculator, a workable solution. However, now there are a number of more automated alternatives, many of them available for free. (See below.) Although an automated tracking system, with your accounts linked to a service like Mint, can save time and give more immediate feedback, you will still need to get things set up to work best for you.

- The right level of detail: Face it, you are not going to know exactly where every penny goes every month. Find the right balance between your time and effort and the level of information you track. If you are someone who balances their checkbook to the penny every month (which is certainly not a bad thing), resist the temptation to have the same level of accuracy tracking your budget.

- Feedback and adjustment: Simply knowing where you spent your money isn't enough. The goal is to track where you spent your money, compare it to your spending plan, and make necessary changes. Allot enough time to review and analyze your performance to determine if it is your spending behavior, or the spending targets that need to be adjusted.

- Communication and accountability: Finally, you need to use this information in a positive way, one that moves you forward toward your goals. Knowing how you are doing relative to your plan should result in meaningful communication and teamwork. You are constantly asking, "What are we doing right?" And, "What do we need to do to differently in order to meet our objectives?" Accountability for spending is generally a good thing, but if couples use the expense tracking to beat each other up, it can become counter-productive.

Tools and links:

- Mint.com--free on-line personal financial tracking system

- Mvelopes--on-line home budgeting system

- Quicken--personal finance software

- YNAB (You Need a Budget)--budgeting system

- Check register (manual) budget tracking system--Montana State University Extension

- Excel home budget templates

- Budget software reviews, with additional links

Creating and following a spending plan may sound like a lot of sacrifice and hard work. Maybe it is. But, when you take active ownership and control over your spending it pays enormous financial and emotional rewards. In times of significant financial uncertainty--and, is there ever a time that is not uncertain--your spending decisions are the one thing you have control over. As Bill Schultheis of the Coffeehouse Investor encourages his readers: "We focus on the most important aspect of building financial wealth--how we save and spend our money."

While biking over to the trailheads at Military Reserve we pass by an old home that we marvel at. Several years ago this building was an eyesore--more likely to house a meth lab than a family. About five years ago somebody with ambition and vision took possession of the house. At first progress appeared slow, with more dismantling being done than construction. However after the first couple of years you saw some tremendous leaps forward as new siding and windows were installed and a second story went up over the garage. The next year there were new decks, fences, and sod was laid. The place now looks great, and we almost always comment on as we ride by.

I don't know who these people are, but they definitely had a plan and stuck with it. They did a lot of hard work as they could commit their time and money. I'm sure they got discouraged at times, and probably made a number changes along the way. But, wow, look where they are today.

You know where I'm going with this. With vision, planning, along with some hard work and sacrifice, these folks transformed a house no one could live in to one they can be exceedingly proud of. You can do the same with your financial house. Even if it is in as tough of shape as that old house, you can turn things around. Are you ready to get started?

Creating and documenting the plan

"He who fails to plan, plans to fail." -- Winston Churchill

"If you don't know where you are going, you might wind up someplace else." -- Yogi Berra

Many people say they have a budget, but it is in their heads, not on paper. Maybe your life is simple enough that this approach works for you, but for most of us it is not effective. If you are not making the progress toward your financial goals that you desire, it is difficult to imagine you are going to turn things around without a written spending plan. The fact is our financial lives are complex, and getting the numbers to add up right can take a while, especially in the beginning. Dave Ramsey, who has helped thousands get out of debt and make serious progress toward "financial peace" following his "baby steps", tells everyone to start each month with a written plan where every dollar has a name (i.e. purpose). This does take some work--but, then don't most things worth achieving?

Key considerations and behaviors:

- Set aside adequate time: Recognize that creating your spending plan is going to take some time and effort--more so to start, but also on an on-going basis. Like cleaning the bathroom or weeding the garden, this may not sound like fun. Hopefully, as you gain experience and control of your finances, it will become less of a burden. You will likely find it useful to break the task of creating the plan into two components--the budget decision meeting and documenting the detailed plan--and setting aside a dedicated time every month for each.

- The budget decision meeting is where you work through hard task of deciding what you are and aren't going to spend your money on. If you are a couple, you both must show up and be engaged in this effort. Both of your interests and concerns must be heard, and no one should run roughshod over the other. It is critical you are both bought into the plan and are accountable. You both have to own it.

- Documenting the detailed plan is where the numbers are put on paper (or on the screen) in a format you both can understand. However, one of you may better equipped or more inclined for this kind of analytical, detailed work. If fact, you may only get frustrated trying to do this together. The format isn't all that critical, but things need to add up correctly and make sense to both of you. (See below for some helpful tools for getting started.) Your goal is to create a working document you can use in the decision meeting to lay out the choices and decisions you are going to have to make. After you make the required trade-offs, they are then documented in the detailed plan. The end result is a written plan where both of you are know how exactly much money you intend to spend, and on what.

- Getting started: You should have a pretty good idea of what you currently spend your money on by looking at your checkbook or debit card transactions and credit card statements. Although a few months will capture most of your recurring expenses, it is helpful to look back over an entire year so you can capture those intermittent expenses that you will also need to be planning for. Remember, the goal here is not just figuring out what you have been spending your money on--it is deciding where you are going to spend your money in the future.

- If you have difficulty accounting for a significant amount of your cash expenditures, you may find it helpful to track your cash (and possibly your credit and debit card expenditures) for a month or two. Keep a note card with you to write down everything you spend as you go through the week.

- You want to break down your expenses into several key categories. How many is up to you--but, not too many, not too few. If you want help with this, check out some of the tools and forms below to get you started.

- Get help if you need it. If you are having trouble getting started, don't be afraid to seek out someone you feel is capable and trustworthy to give you a hand. Or, you might get assistance through community organizations, your church (or Crown Financial Ministries), or through Dave Ramsey's Financial Peace University.

- Plan for irregular income and expenses: If every month looked the same, budgeting would be much easier. For many, the income side of things is pretty stable, but for those on commission or self-employed it can be a roller coaster. Adapting can get a bit complex, but there are different strategies for dealing with this issue. For example, you may create a budget around a base level of income, and then prioritize how you will spend or save any additional income. Creating a savings bucket that enables you to smooth out the available funds each month is another strategy. Planning for irregular expenses (such as insurance payments, vacations, or back-to-school clothes) is a bit easier, but still takes foresight and planning. You basically want to smooth things out by purposely saving ahead of time, or you may be able to arrange for a vendor (e.g. utilities or insurance companies) to bill you a consistent, monthly amount.

- Forget the perfect plan: It will be remarkable if you get this plan perfect to start. You are going to miss things, and you are going to change your mind as you go along. Anyway, the goal isn't a perfect plan--the goal is to be in control of your spending. Forgive yourself, each other, and move forward. This is an on-going process where you seek to remain in agreement over time.

- Plan for some fun: Sure, if want to achieve your goals, you will likely have to sacrifice. However, this doesn't mean you can't enjoy life--you just want to be in control. Usually this is a combination of leaving some money in the budget for recreation and entertainment, plus identifying creative ways to have fun for free (or on a dime).

- Prioritize savings in your plan: Whether it is short term savings to account for irregular income and expenses, building an emergency fund, or longer term savings for college or retirement, savings has to be top-of-mind. Of course, you may have to get expenses under control and/or pay down significant debt first, but the objective is to become a consistent saver. Savings goals must have a prominent place in your documented plan, even if they are on-hold for a while.

Tools and links:

- Dave Ramsey's budget forms and Total Money Makeover

- Developing a Spending Plan and Schedule of Non-Monthly Family Living Expenses, from Montana State University Extension

- Elizabeth Warren's 50/30/20 budget, plus on-line tool

- National Foundation for Credit Counseling on-line budget worksheet

- You Need a Budget, 2011 About.com Readers' Choice for "Best Windows Personal Finance Software" with free trial

In case you missed them, you may wish to check out the initial article in this series, along with Budgeting Fundamental #1--Prioritizing Needs and Wants. Next in this series will cover the final two fundamental elements of budgeting--executing the plan, plus and tracking your performance. Then, I promise to move on to a topic that is less tedious and guilt-ridden. Maybe something on the Black-Scholes options pricing formula.

The foundation of financial success is pretty darn simple. You spend less than you earn, and then put the surplus aside for longer term goals and priorities. Having a spending plan, or budget, is just an on-going discipline that successful people employ to make this happen.

In this article the first of four fundamental elements of the budgeting process--prioritizing your needs and wants--will be covered. The remaining fundamentals will be covered in later posts.

Prioritizing your needs and wants

"It's not how much money you make that matters, but how you make do with what you have." - Big Mama (Michelle Singletary's grandmother)

"Plan for the future, because that's where you are going to spend the rest of your life." - Mark Twain

The first fundamental element of a successful spending plan is the prioritiziation of the many competing interests for your paycheck. Instead of just trying to figure out where you currently spend your money (although this is a good exercise), you need to decide where you should spend your money. There is no substitute for this critical exercise in family strategic planning. If you are single, this may be a lonely exercise, but it is generally much simpler. If you are married, this must be a team endeavor--usually involving a generous amount of negotiation and compromise.

Key considerations and behaviors:

- Setting goals: Creating your spending plan starts with setting goals. What do you want to accomplish with your life and money? Where do you want to be in a year, three years, five years, or twenty years? Listing, discussing, and agreeing upon goals is critical before you start making the important decisions on where you will spend your limited resources.

- Making trade-offs: Creating a spending plan is about prioritizing your needs and wants. It is about agreeing on what you will spend money on, and (maybe more importantly) what you will not spend money on. There is no getting around the fact this can be very difficult, especially if your resources are considerably less than your perceived requirements. As hard as this may be, you will be happier making a well considered spending decision up front, then an undisciplined one on-the-fly. It often takes a purposeful decision to sacrifice today, in order to win tomorrow.

- Agreeing on a core set of values: Spend some time discussing and agreeing on a core set of values for how you are going to manage and spend your money. This may come easy for some, but can be a real stretch for others. However, an agreement on these core values will guide you in the trade-offs you will inevitably have to make. Some the areas you may consider here are:

- Debt--When is when it is acceptable to use debt? How high of a priority it is to get out of debt?

- Financial security--How important is it for you to have financial margin in your life? For example, having a well funded emergency savings account, or plenty of "buffer" in your monthly budget for unforeseen expenses.

- Giving--Will you give to the church or other charities on a regular basis? How will these commitments be prioritized relative to spending and saving?

- Fun--How much importance will you place on fun experiences today relative to making progress on financial goals that are in the future? (Yes, you can budget in some fun!)

- Work/life balance--The trade-off between career demands (and more money) and family time and less stress.

- Anticipating the future: Planning is a about preparing for the future. In creating your budget, you need to spend adequate time anticipating your future needs and wants. Some of these requirements are pretty easy to predict--e.g. the big auto insurance bill that comes every February and August. Others require you to consider what likely lies around the bend in the road--e.g. new tires, a repair bill, or even new shoes for your children. Of course, even further down the road may be a down payment for a house, college expenses, and eventually retirement. You don't exactly know when, but you know these things are out there. You may not be in a position to save for all of them today, but you want to keep them on the radar.

- Teamwork and communication: If you are single, prioritizing your spending may be difficult, but it is a fairly straight forward exercise--you make all the decisions. For couples, this is a major test of your commitment, teamwork, and communication skills. One member of the team cannot "opt out" and leave the responsibility to the other. Both must show up ready to work and compromise. Prioritizing your scarce resources often means sacrificing your needs for the needs of your partner. Learning to work together effectively as a team, is not only powerful in meeting your goals, but can really build your relationship.

Tools and links:

- Personal Budgeting: How to Set Financial Goals

- Setting Your Financial Goals with a Goals Worksheet

- Values and Personal Finance: Letting Values Determine Goals

The next in this series will cover the second fundamental element of budgeting--creating and documenting the plan.

While looking around the web for useful tools and articles on budgeting, I came upon this gem at Investopedia. In the collection of articles under the heading of "Budgeting 101" is this explanatory lead-in:

"With very little effort or sacrifice, budgeting allows you to plan for your future, pay off your debts, and still enjoy life today."

Oh, if it was only so easy.

Let's be clear--budgeting is not about making your life easy, or hard for that matter. It's about being purposeful with your money so you can meet your life goals. Budgeting is also about looking down the road, imagining the life you want, and setting the financial course to get there. Generally, if you are serious about getting somewhere in life, you do some level of planning. Budgeting is simply creating and following a spending plan that supports your life objectives and values.

When you mention the word "budget", people think of several different things. They may associate a budget with a complicated spreadsheet or several labeled envelopes with their monthly cash allotments. The more digitally adept associate budgeting with having all their accounts set up and tracked in Mint.com or Quicken. More than likely, the term "budget" brings on visions of tedious sacrifices such as skipping your morning latte or taking your lunch to work. No wonder people hate budgeting--they see it as a spending diet. (And, unfortunately for many, it is often as ineffective as dieting.)

One of the reasons people struggle with creating and following an effective spending plan is they have an incomplete view of the process. They focus on just one facet of budgeting, but miss the big picture. You will likely find it helpful to organize your thinking about creating and following a spending plan into these four fundamental elements:

- Prioritizing your needs and wants

- Creating and documenting the plan

- Executing and living the plan

- Tracking your performance

A successful spending plan will incorporate all four of these elements, but each person may find it practical to invest more effort in a particular area. The first two elements focus on developing the plan and will be covered in the next post, and the next. The third and fourth elements are about living out the plan, and will be dealt with in the final article.

In the meantime, you may want to check out this short Dave Ramsey budgeting video, just to get into the mood.

Are you looking to improve your financial knowledge and start planning for a brighter future, but not sure how to start? There are plenty of good sources of financial planning information on the web, however sorting through all the junk out there can be difficult. Here are three places to look for free webinars and podcasts, and you can trust the sources.

The National Association of Personal Financial Advisors (NAPFA) started a consumer webinar series earlier this month. You can sign up and watch the webinars live, which gives you the opportunity to interact and ask questions. Or, you can choose a webinar that looks interesting from their archive. The first five topics are:

- Money 101: Knowing the Basics

- Kids and Money

- What is Financial Planning?

- Protecting What You Have (life, health, and medical insurance)

- Investments: The Basics (stocks, bonds and mutual funds)

The Certified Financial Planner (CFP) Board also has a consumer webcast series covering various financial planning topics and presented by CFP(R) professionals. The first four of the 50 minute webcasts covered:

- Managing Debt: From Credit Cards to Foreclosures

- Planning for Your Financial Goals

- Young Professionals: Launching Your Financial Plan

- What to Know When Choosing a Financial Planner

There is an excellent series of podcasts available on the Vanguard investor site, called Plain Talk on Investing. You can subscribe to the podcasts or go out and listen on-line. They are all short (usually ten minutes or less) and generally very informative. Although many cover investing related topics (e.g. investing strategy, mutual funds, bonds, IRAs, etc), you'll also find information on estate planning, college saving, preparing for retirement, and other financial planning issues. To give you a flavor, here are a few of the recent episodes:

- Is "buy and hold" still the way to go?

- Managing withdrawals in retirement

- Saving for college automatically

- New to investing? Learn how to get started

- Estate planning in tough economic times

- How to maximize your retirement savings

Give some of these a try, and improve your financial IQ without cracking a book.

There are many things to like about Vanguard. First it has the best line-up of very low cost index mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) available to individual investors. For those of us who don't want to spend our energy (and our money) chasing the elusive promise of active fund management, Vanguard is a favorite partner. The company has excellent customer service and a good website for the do-it-yourself investor.

Next, you have to love John Bogle, the man who created Vanguard. The more you learn about Bogle and the more you listen to his insight into the mutual fund business, not to mention his common sense wisdom on investing, you begin to realize this man is different. Bogle is truly a leader, and arguably the best friend the individual investor has on Wall Street. You've probably already figured out that most of the financial services industry is not really on your side, but it's frightening to think what the industry would look like without Bogle blazing a different trail.

What you may not realize is that Vanguard is truly unique among mutual funds companies in regards to its corporate structure. The typical fund company is either privately or publicly owned, with its shareholders looking to earn a profit from their investment. There is nothing wrong with that, however the profit objective of the mutual fund company owners generally leads to higher management expenses which, of course, are deducted from the investment returns of the mutual funds. Vanguard is different, however.

Vanguard is actually owned by each of its mutual funds, which are in turn are owned by the mutual fund shareholders (i.e. you and I). This makes Vanguard's organization similar to a mutual insurance company, where the corporation is owned by its policy holders. The profits of the company are distributed back to the mutual funds, lowering their overall cost structure. This is why Vanguard is a true cost leader, allowing investors to reap a larger share of market returns. This structure certainly aligns the interests of the fund shareholders and Vanguard, but unfortunately this mutual mutual fund approach has not been emulated by other fund companies.

Vanguard may seem a bit boring, with its conservative style and all those index funds. (They do have actively managed funds, also.) But, the company has been a true pioneer, leading the move away from broker sold, commission-based (load) funds to low cost, no-load, direct investor-purchased mutual funds. Next time you're complaining about Wall Street, remember there is at least one company there which is truly different.

Next page: Disclosures