Financial Planning Blog

In Part 1, the complex set of rules surrounding Social Security survivor benefits was explored. Survivor benefits can be crucial in providing an economic safety net for families that lose a provider’s income. In this post, we will look at some tips for making the most of the survivor benefits potentially available to you. But first, it is important to clarify exactly what a person must do for their family to be eligible to receive Social Security survivor benefits.

Worker eligibility

- A worker generally becomes eligible for Social Security retirement benefits after earning 40 work credits--or 10 full years. Work credits are earned by working in “covered” employment (including self-employment) where Social Security taxes are paid.

- However, the amount of credits a worker must have accumulated for his dependents to receive survivor benefits depends on the age of the worker at death. The younger a worker is, the fewer credits are necessary for the family to be eligible for survivor benefits. For example, a worker under age 28 would only need 6 work credits, at age 34 it is 12 credits, and at 46 it is 24 credits. If the worker dies at age 62, 40 work credits are required--the same as for retirement benefits.

- Finally, there is a special rule allowing a deceased worker’s children and spouse caring for children to receive benefits even if the worker didn’t have the number of required credits. In this situation with dependent children, benefits are available as long as the worker simply had accumulated 6 credits (1.5 years of work) in the three years prior to death.

Planning tips

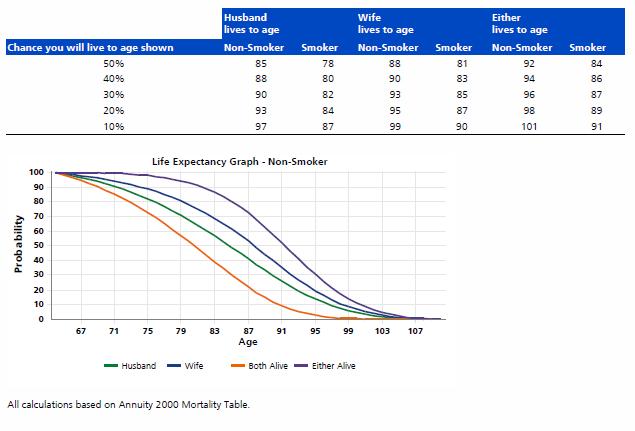

- While still alive, have the highest earner maximize their benefit. Although the majority of people choose to start their retirement benefits early, with married couples it is often wise to maximize the higher of the two benefits. This entails having the spouse with the highest earned benefit wait until 70, gaining delayed retirement credits. This maximized benefit will then be available across both spouses’ lifetimes. This is the most cost effective way to secure a healthy inflation adjusted lifetime income stream that will protect a couple from longevity risk. This strategy is most compelling when the higher earner is the older spouse, and has a shorter expected lifespan (often the male).

- Coordinate survivor and personal benefits wisely. If you are eligible for both a personal benefit off of your own work record and a survivor benefit off of a deceased spouse’s work record, you have an important opportunity maximize the long term value of the combined Social Security benefit stream. The general rule is to maximize the larger of the two benefits by waiting to start it at the most opportune time. Compare what your personal benefit will be if you wait until age 70 (maximized with delayed retirement credits) with the survivor benefit at your full retirement age (FRA—after which it will not grow). If your maximized personal benefit is the highest, delay taking it until age 70. In the meantime, start taking the survivor benefit as early as age 60 (usually as soon as you stop working), then switching to your own benefit at 70. If the survivor benefit at FRA will be the highest amount available to you, wait until FRA to start it. In the meantime, you can start your personal benefit at age 62. Using this strategy, you benefit from the largest possible retirement benefit for the longest possible time.

- Your survivor benefit may not be maximized at your FRA. If your deceased spouse started his or her benefit prior to their FRA (and many, many do), then are situations when it will not make sense to wait until FRA to start. (Remember the widow(er)’s limit provision mentioned in Part 1.) For example, if your spouse filed early enough, your benefit may never be larger than 82.5% of their PIA. Your survivor benefit may be maximized at this 82.5% a few years earlier than your FRA, and it may not make sense to wait any longer to start taking it. This is complex, so if your deceased spouse started taking retirement benefits early and you have yet to reach your FRA, contact the SSA and have them calculate when your survivor benefit will be maximized.

- Be mindful of the earnings test. In the years prior to hitting your FRA survivor benefits are subject to the earnings test. If you are still working, it may be counter-productive to start taking survivor benefits if you are going to lose $1 of benefits for every $2 you earn over the limit (in 2012 it is $14,640). Depending on the situation, it may, or may not, make sense to start receiving benefits if you are still working. It may be wise to delay starting and let your benefit get larger.

- Get married. Survivor benefits are available to married couples, not to those couples who have chosen not to tie-the-knot. Your decision not to encumber your relationship with the bonds of marriage may prove to be an expensive one, when you consider lost survivor and spousal benefits. Most unmarried couples (at least the ones I talk to) are oblivious to the availability and value of survivor and spousal Social Security benefits.

- Hold it…maybe you don’t want to get married until age 60. Make that remarried. Remarriage prior to age 60 will make you ineligible for survivor benefits off of a deceased spouse’s record. (If that remarriage ends, you will again be eligible for the survivor benefits.) If you are contemplating remarriage and you are getting close to age 60, it might just be worth waiting a few months…or years. It is possible that these survivor benefits may be more valuable than your personal benefit, or any spousal benefits available off of a new spouse’s record. The survivor benefits are also available earlier (age 60) than your personal or spousal benefits (age 62). Don’t underestimate the potential value of wisely coordinating a survivor benefit with your personal benefit.

- Keep track of your ex-spouse. If you were divorced after being married for at least 10 years, you may be eligible for a survivor benefit off of your ex-spouse’s work record, if he or she passes away. Your ex-spouse is dead, and money now starts appearing in your checking account! This may sound too good to be true, but hey, this is America. Again, remarriage prior to age 60 will make you ineligible (unless that marriage ends, also). Don’t count on the SSA to magically find you, though. You will need to contact them and prove your eligibility for a survivor benefit.

- Survivor benefits are listed on your Social Security statement. Although these are not mailed out annually like they used to be, you can always get an updated statement here. Your statement tells you what your spouse and children would be eligible for if you were to die this year.

As discussed in earlier articles, the Social Security System is designed to enhance the economic security of families, not just individuals. Social Security's structure of spousal and survivor benefits does provide a meaningful level of family income protection, but also adds significant complexity to an already complicated system. Unfortunately, a lack of understanding of the Social Security system may result in a failure to access available benefits at a critical time. In this post we want to take a closer look at the rules pertaining to benefits available to family survivors of a deceased worker.

Rules concerning survivor benefits

- A surviving spouse is entitled to a survivor benefit based off the deceased worker's Social Security earnings record. These are often referred to as "widow's benefits", but they also are available to widowers.

- The two must have been married for at least nine months prior to the death, unless the death is due to an accident.

- Remarriage before age 60 disqualifies a widow for survivor benefits. However, if that marriage ends (e.g. a divorce, death of the second spouse) the surviving spouse is again eligible for benefits off the deceased spouse's record.

- Remarriage after 60 does not cause a person to lose eligibility for survivor benefits. That person could continue to receive the survivor benefit, but may also choose to switch to their personal benefit and/or spousal benefits based off of their new spouse's earnings record.

- There is no double-dipping--a person cannot take a survivor benefit and their personal and/or spousal benefit. For example, John dies at age 70 with a $2,500/month benefit, while his 70 year old wife Mary was receiving own benefit of $1,000/month. She would drop her personal benefit and start receiving her survivor benefit of $2,500. She would not get to receive both benefits totaling $3,500.

- If a person is unlucky enough to be widowed multiple times, they are eligible for the highest of the available survivor benefits.

- There are potentially survival benefits available for divorced spouses.

- The size of the survivor benefit is determined by 1) the amount of the deceased worker's retirement benefit, and 2) the age at which the surviving spouse starts the benefits. However, there are some important adjustments and limitations that can make calculating the survivor's benefit pretty complex.

- The survivor benefit is calculated off the prmary insurance amount (PIA), which is the monthly benefit the deceased worker would have received at full retirement age (FRA). If the deceased worker's benefit had been increased with delayed retirement credits (DRCs), then this higher amount (or "deemed life PIA") is used. (This includes the situation where a worker dies past FRA without having started to receive benefits--the deemed life PIA is adjusted upward for DRCs that had been earned up to point-of-death.) What this means is that if a worker delays starting their retirement benefits and earns DRCs, the surviving spouse will ultimately be eligible for a higher survivor benefit.

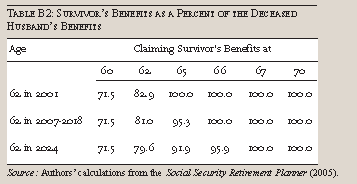

- When a worker dies after receiving reduced benefits (i.e. retirement benefits were reduced for starting prior to FRA), the deceased worker's PIA is still the base for calculating the survivor benefit. However, the deceased worker's actual reduced benefit will be a limiting factor on the ultimate benefit available to the surviving spouse. This is because of an obscure, but very important rule called the widow(er)'s limit provision. The survivor benefit will never be higher than the larger of the deceased worker's actual benefit or 82.5% of the deceased's PIA. (This is meant to prevent, or at least limit, situations where the survivor benefit is higher than the actual benefit the deceased worker was receiving.) What this means is a worker's decision to take early benefits will reduce the potential survivor benefits available to their spouse.

- If the surviving spouse waits until their own FRA*, they will receive the full survivor benefit--i.e. 100% of the deceased spouse's PIA (adjusted upward for any DRCs). However, in the situation where the worker had taken early reduced benefits, the widow(er)'s limit provision basically reduces the full survivor benefit to the level of the deceased worker's actual benefit, but not below 82.5% of the PIA. (Got that?) Important to note is that unlike a person's personal benefit, there is no advantage to waiting longer--the survivor benefit will not continue to grow past one's FRA (i.e. there are no delayed retirement credits with survivor benefits).

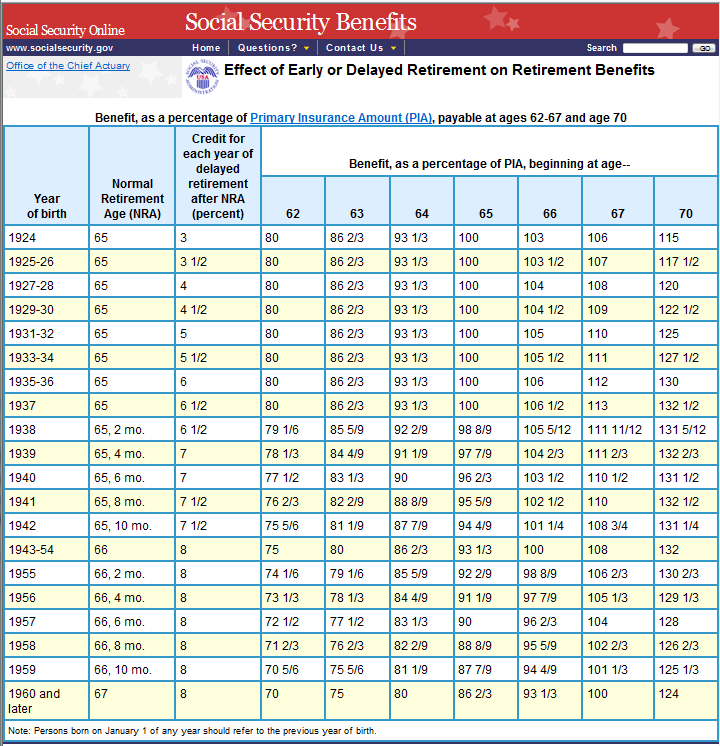

- A surviving spouse can generally start receiving benefits as early as age 60. If a surviving spouse chooses to start receiving survivor benefits prior to FRA, the benefit is reduced up to 28.5% (to 71.5% of the full survivor benefit), depending upon how early they choose to start. (See this chart for details on the exact monthly reductions by birth year.) Even if the deceased worker had started reduced benefits at the earliest age (62), and the surviving spouse starts survivor benefits at the earliest possible age (60), the survivor benefit is never lower than 71.5% of the worker's PIA.

- The survivor benefit is calculated off the prmary insurance amount (PIA), which is the monthly benefit the deceased worker would have received at full retirement age (FRA). If the deceased worker's benefit had been increased with delayed retirement credits (DRCs), then this higher amount (or "deemed life PIA") is used. (This includes the situation where a worker dies past FRA without having started to receive benefits--the deemed life PIA is adjusted upward for DRCs that had been earned up to point-of-death.) What this means is that if a worker delays starting their retirement benefits and earns DRCs, the surviving spouse will ultimately be eligible for a higher survivor benefit.

- There are some special rules that allow surviving spouses to receive benefits prior to age 60.

- If the surviving spouse is disabled, they can start receiving benefits as early as age 50. Any benefit prior to age 60 would generally be 71.5% of the PIA.

- If the surviving spouse who is not yet age 60 is still caring for the children of the deceased spouse, he or she is eligible for 75% of the deceased's PIA until the child reaches the age of 16. (Or any age if the child becomes disabled prior to age 22.)

- Surviving spouses are not the only ones entitled to benefits off a deceased person's Social Security earnings record. The deceased's children and dependent parents may also receive benefits.

- Children of the deceased worker who are under age 18 (age 19 if still in high school) are eligible for a benefit equal to 75% of the deceased worker's PIA . (The child must also be unmarried.)

- A disabled child may receive the same 75% benefit at any age, as long as he or she became disabled prior to age 22 and remains disabled.

- Believe it or not, some parents may receive benefits off of their children's earnings records. If the deceased worker was providing greater than 50% of the support for a parent over age 62, then that parent may receive a benefit of 82.5% of the worker's PIA. If both parents were supported by the deceased worker, each is entitled to a benefit of 75% of the worker's PIA. Of course, if the parents were entitled to larger benefits off of their personal records, they would continue to receive them instead. They would not be able to receive a survivor benefit and their personal or spousal benefits at the same time.

- A special one- time lump sum death payment of $255 is also available to surviving spouses who were living in the same household with the deceased worker at the time of death. If there is no spouse eligible for this benefit, it may be paid to a child (or children) eligible to receive benefits off the deceased's record.

Some limiting factors

As you can see, a number of people might be eligible to receive survivor benefits off of a deceased person's Social Security earnings record. These survivor benefits, when added together, could far exceed the benefits the deceased person would have received if they remained alive. However, there are a couple of important rules that limit the amount of benefits available to survivors.

- There is a maximum family benefit--the maximum monthly amount that can be paid on a particular worker's earnings record. This applies not only to survivor benefits, but also when a beneficiary is alive and receiving benefits. (There is a different maximum family benefit payable to a family of a disabled worker.) This is an excessively complicated formula, but the gist of it is that the family maximums range from 150% to about 180% of the deceased workers PIA.

- For example, consider a deceased worker with a PIA of $2,000/month, who leaves a surviving spouse below the age of 60, and three children under the age of 16.

- Each would be eligible for a benefit equal to 75% of $2,000, or $1,500/month. Combined these four benefits would equal $6,000/month, or 300% of the deceased's PIA.

- However, the family maximum benefit in this situation would be about 175% of the deceased worker's PIA, or $3,500/month. In such situations, each benefit is adjusted proportionately to bring the total within the limits.

- There is the earnings test--which can mean lower benefits if a beneficiary works and earns too much in a year. Just as regular retirement benefits are subject to the earnings test, so are survivor benefits. This means that if the recipient is below their FRA and they earn over the earnings limit, they would lose some (or all) of their survivor benefits. In 2012 the earnings limit is $14,640 for benefit recipients who are below FRA for the entire year. For every $2 earned above $14,640, there will be $1 of Social Security benefits deducted.

- For example, consider a person receiving $1,000/month ($12,000/year) in survivor benefits. As long as the person earns below $14,640 then there is no impact on their full $1,000/month survivor benefits. If they earn $24,640 for the year, then $5,000 of benefits will be deducted. (This is half of the $10,000 above the limit). If the person earns $24,000 or more above the limit (i.e. $38,640 or more) then their survivor benefit would be entirely lost.

- If the recipient of benefits is past their FRA, then there are no earnings limits. They can earn as much as they want and still receive 100% of the benefits to which they are entitled.

- There are special rules for the year in which a beneficiary hits their FRA.

- Only earnings from work (i.e. wages or self-employment income) count toward the earnings test. Investment earnings, pensions, and other government benefits are not counted toward the limit.

- The earnings test is on an individual, not a household level. As a result, if a surviving spouse earns above the limit it does not impact the benefits of any children also receiving benefits. Also, a person earning above the limit does not impact the Social Security benefits of their spouse.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*As if this isn't complicated enough, your full retirement age as a survivor may be different than your FRA for regular retirement benefits. For example, a person born in 1956 will have a survivor FRA of age 66, but a regular FRA of 66 and 4 months. This is because the birth years for the gradual FRA shifts from age 65 to 66 started in 1943 for regular benefits and in 1945 for survivor benefits. Also, the gradual FRA shift from age 66 to age 67 starts two years later-birth years 1954 for retirement benefits and 1956 for survivor benefits. (Was anyone paying attention when these rules are made?)

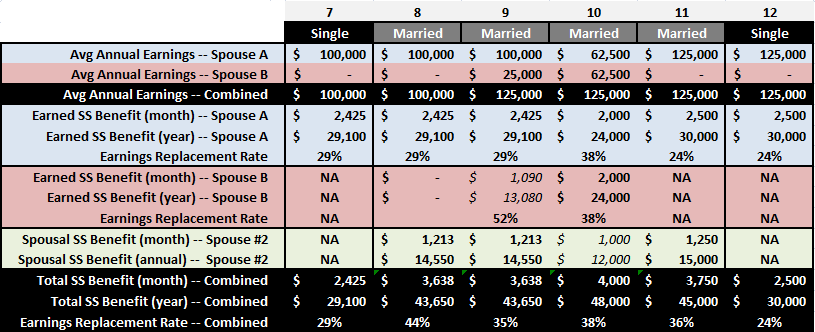

The availability of spousal benefits has a big impact on the percentage of people's pre-retirement income that is replaced by Social Security. In Part 1, we examined "average" income earning singles and couples, and compared combined retirement benefits and replacement rates. We saw how spousal benefits lifted a married couple's combined benefit, but the impact could be very different depending on whether both spouses worked or not. Here we will look at higher earners and see somewhat similar outcomes. And, if you compare the earnings replacement rates of these higher earning singles and couples with the lower earning people in Part 1, you will note that as incomes rise, replacement rates go down. (In other words, the Social Security retirement system is progressive, in that lower income earners receive a higher return on their taxes paid in than upper earners.)

Below are six more singles and couples, these with "high" incomes of $100,000 to $125,000 per year. Again, two of the examples are single workers, while the other four examples are married couples. Two of the married couples have only one working spouse (couples #8 and #11), while the remaining two couples are comprised of dual earners paying into the Social Security system. (The examples assume all are retiring in 2012 at their full retirement age of 66, and they have not yet consulted with Table Rock Financial Planning on ways to make the most of their Social Security benefits.)

- Compare the single individual and the married couple, both making $100K/year (#7 and #8). Assuming their earnings have been the same over their working life, they have paid the same amount of taxes into the Social Security system. However, due to the availability of a spousal benefit, the married couple stands to receive a 50% higher combined benefit. The high earning single person will receive a benefit that replaces about 29% of his or her pre-retirement income, but the married couple will receive combined benefits amounting to a 44% replacement rate. Again, we see that the married wage earner potentially receives a significantly larger return on his or her contributions to the Social Security system. Fair or not, it is how the system is designed. And, if you understand the somewhat complex rules of the system, there are many perfectly legal and ethical opportunities for a married couple to further maximize the potential value of their combined Social Security benefits.

- Next, check out the situation with married couples #8 and #9. Only spouse A worked in couple #8, earning a healthy $100K/year. Couple #9 has an even higher combined income since each spouse worked, earning $100K and $25K respectively. As a result of these work histories, couple #8 has only one spouse with their own earned retirement benefit, but with couple #9 both spouses have earned benefits. Remarkably, even though couple #8 earned less money and paid less into the system, they will have the same combined Social Security benefit as the higher earning couple who both worked and paid more taxes. (Not to be critical, but who designed this system? Could it have been Congress?) Both couples' dollar benefits are equal, but the lower earning couple #8 is receiving benefits that replace 44% of their pre-retirement income, but the higher earning couple #9 is receiving only 35%. What this means is that, all things being equal, couple #9 will need to save more money to maintain a comparable post-retirement lifestyle. Couple #9 appears to get a raw deal here...but, isn't it always that way with entitlements? The other guy always seems to get a better deal from The System. Get used to it. Couple #9 can console themselves and improve their situation by going to a fee-only financial planner that understands the Social Security system.They have some opportunities to increase their income by coordinating their spousal benefits.

- Like couple #9, couples #10 and #11 also earned $125K, but taking different paths to that end. With couple #10, both spouses worked and contributed to the combined income equally. (I'm sure they hyphenated their names and shared the chores equally, also.) In couple #11, the income was earned the old fashioned way--entirely by spouse A. After seeing the previous examples, including the average earners in Part 1, you probably assume these three couples will have wildly different combined Social Security benefits. Not so--they are all pretty close, with replacement rates between 35% and 38% of their pre-retirement incomes. In Part 1, we saw how having the earnings concentrated with one spouse can lead to higher earning replacement rates. However, high earning couple #11 didn't find that to be true. The reason is that high earning spouse A earned over the Social Security maximum taxable earnings over their career, limiting both their Social Security tax liability and their eventual benefit.

- Finally, let's compare the two single individuals (#7 and #12). Even though #12 earned on average 25% more than #7, their retirement benefits are very close to the same. This is fair, since they both probably paid about the same amount of taxes into the system. The higher paid #12 likely earned over the Social Security maximum taxable earnings for entirety of their career, where #7 probably earned close to, but slightly below the limit. However, when you compare their replacement rates, the lower earning #7 fares somewhat better than the higher earning #12--29% versus 24%. The key point here is that both of these high earning single people receive a much lower replacement income from Social Security than their married counterparts (#8-#11), whose combined benefits replace 35% to 45% of the couples' similar incomes. Also, the Social Security retirement benefits these high earning singles receive provide them with a much lower replacement income than the lower (or average) earning singles we saw in Part 1. Higher earners need to save more to replace their pre-retirement incomes than lower earners. And, if you are single, count on having to save even more to replace your income in retirement than your married friends. Otherwise, don't fret about not having a companion to dine out or vacation with--you won't be able to afford it anyway.

If you haven't figured it out yet, the Social Security system is much more complicated than you first thought...if you ever bothered to give it a thought. And, this only scratches the surface. To sum up, here are a few key takeaways:

- If you are single person--save more for retirement.

- If you are a higher earner--save more for retirement.

- Everyone else--save more for retirement. (Just to be sure.)

Social Security benefits are a sizeable chunk of most American's retirement incomes. Before you make the important decisions regarding when to start your benefits, or how to coordinate your benefits with your spouse, make sure you have an adequate understanding of your options. This is a great time to consult with a fee-only financial planner who understands the system, in order to make sure you are doing the most to maximize your personal long term financial security.

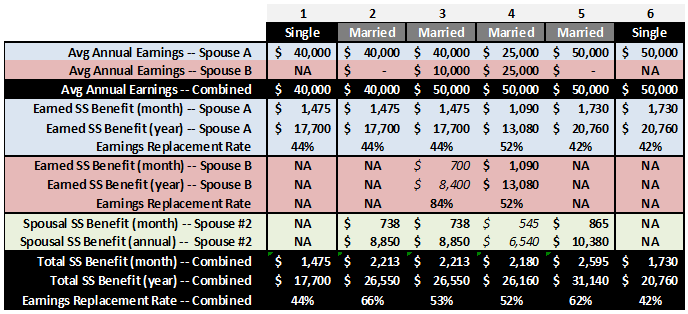

In the previous post, the key rules regarding Social Security spousal benefits were introduced. Although most people are aware that a married worker's spouse can receive a retirement benefit off the worker's record, few appreciate exactly how much this influences the replacement income Social Security provides a family. Some examples will illustrate key points about how marriage, the distribution of income between spouses, and the availability of spousal benefits impact the amount of benefits received from the Social Security system.

Below are six different situations with workers making an "average" income of $40,000 to $50,000 per year. In two of the examples the workers are unmarried, with the other four comprised of married couples. In two of the married couples, one spouse does not work. In the other two married couples, both spouses have earnings covered by Social Security. (It is assumed all are retiring in 2012 at their full retirement age of 66. None of the individuals have been reading financial planning blogs suggesting they wait until 70.)

- Compare the single individual and the married couple, both making $40K/year (#1 and #2). Even though earnings and taxes paid into the Social Security system are the same, the married couple stands to receive a considerable amount more from the system. Due to the availability of the spousal benefit (equal to 50% of the worker's primary insurance amount), the married couple will receive benefits replacing 66% of their pre-retirement income, compared to the single person replacing only 44%. Is this fair? I suppose it depends on whether you are the single person, or part of the married couple.This is a prime example of how Social Security is family oriented.

- Now compare married couple #2 with average earnings of $40K and married couple #3 with average earnings of $50K per year. Notice that spouse B of couple #3 contributed $10K/year of their earnings, and earned their own personal benefit of $700/month. However, spouse B's earned retirement benefit is lower than the $738/month spousal benefit they are eligible for. The Social Security Administration (SSA) will supplement spouse B's earned benefit to bring it up to the $738 spousal benefit. Note that the combined benefits of couples #2 and #3 are equal, even though couple #3 made 25% more money, and presumably paid 25% more into the system. The earnings replacement rate of the lower earning couple #2 is 66%, but drops to only 53% for couple #3. Unfortunately, that part time job for couple #3 didn't contribute as much to their retirement as they had anticipated. Hopefully, they saved a good part of spouse B's earnings.

- Similar to couple #3, couples #4 and #5 also earned $50K, but did so in different ways. In couple #5, only spouse A worked and earned a benefit. In couple #4, both spouses contributed equally to the family finances, both earning $25K/year. Both earn an equal benefit from Social Security, which is higher than the spousal benefit they would be eligible for off the other spouse's record. Note that couple #4, where both spouses worked, has an earnings replacement rate of 52%--slightly lower than couple #3. Couple #5, where only one spouse worked, has a remarkably higher combined earnings replacement rate of 62%--about $400/month more than couples #3 and #4 where both spouses worked. How earnings are split between spouses makes a surprising difference. For these average earning couples, having the earnings concentrated with one spouse leads to higher earnings replacement rates. However, having earnings concentrated with one spouse does not necessarily lead to higher benefits as incomes rise, as you'll see in Part 2.

- Finally, compare the two single individuals (#1 and #6). As expected, the one making $50K/year has earned a higher retirement benefit than the one making $40K/year. However, notice that the earnings replacement rate is a bit lower for the higher earning worker as compared to the lower earning worker (42% versus 44%). Even though Social Security retirement benefits increase with higher average lifetime earnings, the amount of pre-retirement income that is replaced by Social Security significantly declines. As you'll see in Part 2, the replacement rate for a single worker averaging $125K/year drops to under 25%. This is just one way that Social Security benefits are already "means tested"--where higher earning people pay more and/or receive less from the system. Most will agree this is somewhat appropriate, but it is important to consider how much "means testing" is currently in the system before calling for more.

These examples give you an idea of how different factors determine the amount of replacement income people can expect from Social Security. Obviously, it makes a big difference for an individual or couple whether their Social Security benefits will replace 20% or 60% of their pre-retirement income. After all, they need a plan to cover the rest or else face a severe drop in lifestyle in retirement. Next, we will look at a similar set of examples covering higher earning workers and spouses.

One of the more thoughtful and "women friendly" characteristics of the Social Security system is the availability of various types of spousal benefits. These constitute some of the more complex features of the retirement benefit system, but also provide some fruitful planning opportunities.

When the Social Security Act was passed back in 1935, the initial provision of monthly benefits for retirees was set to begin in 1942. This allowed at least a small number of years for payroll taxes to build up a reserve. However, in 1939 the system was amended to pull in the start of monthly payments to 1940, and also added benefits for wives, widows, and dependent children of covered workers. In one fell swoop, Congress set the tone for the next several decades and established two important Social Security trends:

- It is easier to add additional Social Security benefits first, and let others worry about paying for them later. But, hey, before we complain about too much about Congress doing this, we should admit that this simply reflects the will and the behavior of the "average" American.

- The Social Security System is about enhancing the economic security of families, not just individuals. Since the common family model of that time was a working father and a stay-at-home mother, it was important to also ensure the economic well-being of the non-working spouse and children. Interestingly, spousal benefits were initially provided only for women, not for men. (This was changed after Ozzie Nelson organized a massive march on Washington by stay-at-home dads in the mid 1950s.) As a result of spousal and dependent benefits, married workers and their families generally stand to receive more out of the Social Security System than single workers.

Here are the key rules regarding Social Security spousal benefits:

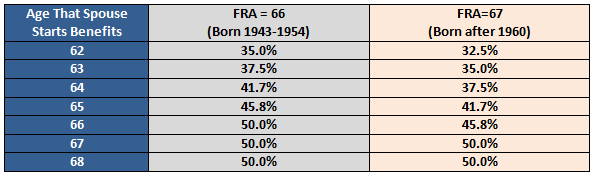

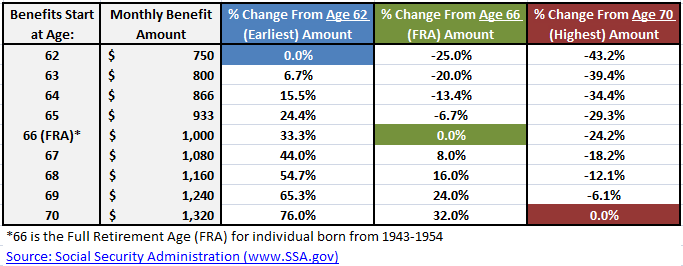

- The spousal benefit is calculated off the retired workers primary insurance amount (PIA), which is the worker's earned retirement benefit at full retirement age (FRA). Full retirement age is 66 for workers born between 1943 and 1954, but transitions to age 67 for younger workers.

- A spouse is eligible for up to 50% of the retired worker's PIA, but the exact amount depends on when the spouse (not the retired worker) files for monthly benefits. At the spouse's full retirement age, the benefit is 50% of their husband or wife's PIA. However, if benefits are taken earlier than FRA they are reduced by 25/36 of one percent for each of the first 36 months. After 36 months, the reduction is only 15/36 of one percent per month. The table below shows the percentage of the worker's PIA spouses can expect, depending on when they start benefits, and whether their own FRA is at age 66 or age 67.

- Waiting beyond FRA does not increase the spousal benefit. This is in contrast to a worker's own benefit that can grow considerably from FRA to age 70 with delayed retirement credits. Even if the worker delays until age 70, maximizing his or her personal benefit with delayed credits, the spousal benefit will not increase--it is always calculated off the worker's PIA. Conversely, the spousal benefit is not reduced if the worker chooses to claim a reduced benefit as early as age 62.

- Age 62 is the earliest a person can apply for spousal benefits, unless they are caring for a "qualifying child"--i.e. a dependent child under the age of 16, or one receiving Social Security disability benefits. Unlike normal spousal benefits, if the spouse is caring for a qualifying child the benefit is not reduced for early receipt.

- Generally, a spouse must be married to the worker for at least one continuous year prior to applying for benefits. This requirement is waived if the spouse is already receiving survivor benefits or spousal benefits off an ex-spouse's work record.

- The spouse cannot claim benefits until the worker is "entitled" to benefits. In other words, the worker with the earned benefit must either be receiving benefits, or have filed for, but suspended receipt of his or her benefit. (More on why someone would the "claim and suspend" later.)

- If the spouse is working and has not yet hit their FRA, any spousal benefits they receive may be reduced if they exceed Social Security earnings limitations ($14,640 for 2012.)

In the next post we will look at some of the implications of the spousal benefits, along with how cultural trends will impact the amount of "replacement income" that Social Security will likely provide future individuals and families. And, if you are wondering about how retirement benefits work for divorced spouses and widows (and widowers), these will also be examined in coming weeks. Finally, we will look at some of the planning opportunities provided by the very thoughtful, but very complex Social Security retirement system.

In the last post we explored a number of reasons why the 4% rule may be too conservative. Although it would be nice to leave you on such a positive note, it is worthwhile to balance this with a more cautious perspective.

Why a 4% safe withdrawal rate may be too optimistic

Most safe or sustainable withdrawal rate studies are based on historical data, and the general assumption is that future returns will be similar to the past. Two issues with this approach are identified by a number of researchers.

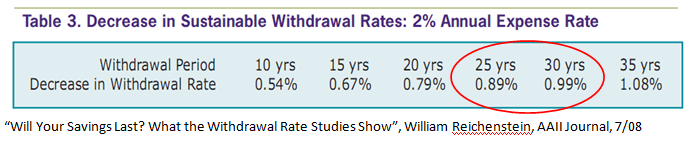

First, many (but, not all) safe withdrawal rate studies ignore the impact of that investment costs have on investor returns. On average, investors will not earn the gross return to stock market index, but rather a net return after costs. Between mutual transaction costs, mutual fund expenses, and potentially investment management fees, it is easy to imagine a drag of at least 1% to 2%. William Reichenstein of Baylor University calculates that if you assume investment returns are 2% lower than the historical gross (i.e. before investment costs) returns, then sustainable withdrawal rates over 25 to 30 year periods are about 1% lower. In other words, your 4% to 4.5% safe withdrawal rate becomes 3% to 3.5%.

Second, there is no guarantee that future market returns will be as generous as the past hundred or so years of data. In fact, many influential investment managers and economists expect lower market returns over the next ten to twenty years. They point to historically low dividend yields, high stock market valuations (i.e. price to earnings ratios, or the amount investors are paying for a dollar of corporate earnings), low interest rates, and concerns over future economic growth as harbingers of lower future stock and bond market returns. Here is a sample of prominent voices on this subject:

- John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, expects future stock market returns to be around 7%, compared to historical returns or 9% to 10%. In a 2009 Morningstar video he stated: "I think we give far more credence to past returns in the stock market than they even remotely deserve. The past is not prologue. The stock market is not an actuarial table." Rather than looking at past returns, Bogle says we need to focus on the sources* of past and future stock market returns. We can, and should, have reasonable and rational expectations of these sources of returns.

- Ed Easterling of Crestmont Holdings points to relatively high stock market valuations, the current low interest rate environment, and uncertainty of future economic growth as reasons to be very cautious with future expectations. In a recent Wall Street Journal article he says, "Retirees, especially those that started in the recent past, have a relatively long period ahead of them. Over-assumed returns can empty savings more quickly than many expect." With the conditions of the past few years, he believes a safe withdrawal rate is 3% or less. (If you have access to the AAII Journal, see Easterling's September, 2011 contribution: "Historical Performance and Future Stock Market Return Uncertainties.")

- Rob Arnott and John West of Research Affiliates also don't believe future returns will match expectations set blindly on historical data. In "Hope is Not a Strategy" they derive baseline return assumptions for large U.S. stocks of only 5.2% (or a 3.2% real return after inflation). For bonds, they have a baseline assumption of only 2.5%. "The only way today's expected returns can match tomorrow's targeted returns is through remarkable good fortune in the years ahead. We're relying on hope. But hope is not a strategy; hope will not fund secure retirements. We're planning for the best and denying that worse can happen. It makes far more sense to hope for the best, with plans for realistic outcomes-and contingency plans for worse ones."

- Bill Gross of PIMCO has been talking about a "new normal" period of slower economic growth and lower market returns for both stocks and bonds. "Instead of 10% returns for stocks, look for five or so. And instead of the past 20 years' returns on bonds, which are actually better than stocks -- close to double digits -- it's 4% going forward. So that's what the new normal is. And it's based upon the primary assumptions of a deleveraging of the private sector and the public sector being limited in what it can spend."

This just brings home the fact that future market returns are not some sort of entitlement. We don't know what the next 10 to 20 years has in store in regards to market returns, but it is probably unwise to presume that the future will deliver historically healthy results. Although the concept of a safe withdrawal rates is a tool to deal with these risks and uncertainties, there may be reason to be a bit more cautious. (For one such cautious approach, see this video where Ken French of Dartmouth discusses establishing a safe withdrawal rate starting with Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or TIPs.)

As discussed in Part 2, it is unrealistic for someone to set a withdrawal rate and leave it untouched for 30 years. For a successful outcome (i.e. one that doesn't involve moving in with your children or becoming a regular at the food bank), it is important to be attentive and flexible. If the markets are not delivering adequate returns over the first critical 10 to 15 years of retirement, you will certainly be getting real time feedback on your account statements. If that doesn't alert you to cut back a bit on spending, take the hint when your financial advisor suggests you look into jobs at Walmart.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

*Bogle breaks the the sources of stock market return into:

- Investment return, which comes from initial dividend yield and future earnings growth.

- Speculative return, which comes from the change in the public's valuation of stocks, measured by the price/earnings ratio--basically how much investors are willing to pay for each dollar of corporate earnings.

In days gone by many retirees could rely on the three legged stool of retirement income--Social Security, personal savings, and company or government pensions. For private sector workers especially, this third leg--employer defined benefit pension plans providing guaranteed lifetime income--is becoming increasingly rare. More and more retired people are now required to manage their personal savings (often accumulated in IRAs or employer defined contribution plans like 401Ks) to cover a majority of their expenses over a potentially long retirement. This is not an easy task, and it isn't obvious how much retirees can spend each year from investment portfolios without running the risk of running out of money before running out of years (i.e. shortfall risk).

In Part 1 a popular rule of thumb for sustainable portfolio withdrawals, the 4% rule, was discussed. Now calling the 4% rule "popular" is a bit misleading. It is popular in the same vein that other often repeated rules like "floss daily" and "stay within 5 MPH of the speed limit" are popular. People don't like the 4% rule because it seems very conservative, very restricting, and a major obstacle to enjoying retirement. When they realize that the 4% rule implies you need a portfolio 25 times the beginning portfolio withdrawal-people exclaim, "No way, that is just not going to happen!"

Never fear, many respected financial planners agree that the 4% rule is a bit too cautious. Below is a brief rundown of some of the criticism.

Some reasons the 4% rule may be too conservative

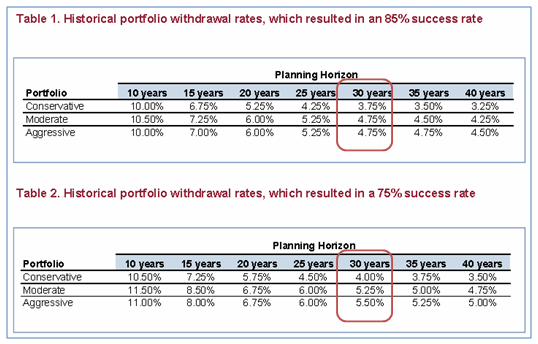

First of all, the historical data shows with a beginning withdrawal rate of 4%, portfolios would have successfully sustained inflation adjusted withdrawals for 30 years 90%-95% of the time. As the following Vanguard tables show, 4.75% to 5.25% withdrawal rates (with moderate -- 50% stock/50% bond portfolios) were sustainable over 30 years with 75% or 85% success rates. (Not bullet-proof, but successful most of the time.) In fact, you'll often hear the 4% rule quoted as suggesting beginning withdrawals of 4.5%, or 4% to 5%.

Research Note: Revisiting the ‘4% Spending Rule' (Portfolio allocation: Moderate portfolio = 50%/50% stock/bonds, Conservative portfolio=20%/80%, Aggressive=80%/20%)

A common, and valid, criticism of the whole "safe withdrawal rate" concept is that a static withdrawal rate over 20-40 years is simply unrealistic. Or, as Moshe Milevsky says, "...a simple rule that advises all retirees to spend x% of their nestegg, adjusted up or down in some ad hoc manner, is akin to the broken clock which tells time correctly only twice a day." Certainly, retirement expenses are not linear over time, and many argue that expenses are often higher in the early years of retirement when people are more active. Maybe rational retirees would prefer to have more spending early in retirement, and willingly accept lower spending budgets later in retirement, if necessary. To impose a 30 year linear budget is not only a bit rigid, but will more likely than not, result in a substantial surplus at the end of the plan.

If you are flexible and disciplined, you can do better than starting out with only a 4% portfolio withdrawal rate. You simply have to be willing and able to cut back if subpar portfolio performance demands it. Jonathan Guyton has done some of the best research defining relatively simple decision rules governing spending rates which, if followed, can significantly increase the beginning withdrawal rate. Guyton starts with a basic withdrawal rule that says withdrawals are modified upward for inflation, except following years where the portfolio return is negative. Any missed inflation adjustments are not "made-up", but he has two other decision rules (or "guardrails") that work to keep withdrawals from becoming too high or too conservative. The first guard rail is the capital preservation rule which calls for a 10% reduction from the previous year's withdrawal when the withdrawal rate gets too high (20% above the starting rate). In good times the prosperity rule kicks in, calling for a 10% increase in withdrawals when the current withdrawal rate drops too low (20% below the beginning rate). Guyton's research says that these decision rules will provide for 30 year withdrawal periods at beginning rates ranging from 4.6% to 6.5%, with the expectation that the capital preservation rule (i.e. 10% cuts) is triggered no more than 10% of the time. The lower starting withdrawal rate is for moderate portfolios (50% stock) and very high probability for success. The higher starting withdrawal rates require higher allocations to stock and/or somewhat lower probabilities of success (but still 90% or above).

Finally, another bit of research that points to potentially higher safe withdrawal rates was done by influential financial planner Michael Kitces in 2008. Kitces drew on research that has shown an "incredibly strong inverse relationship" between the starting price to earnings ratio of the S&P 500 and the following 15 year returns. Since it is sequence risk, or the risk of lousy market returns during the first 15 years of retirement, that deplete portfolios prematurely, P/E ratios could be an excellent predictor of potential failure. (The analysis uses a P/E ratio based on the 10 year average of real earnings, referred to as P/E10 or CAPE-the Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings Ratio.) Indeed, Kitces found that "the only instances in history that a safe withdrawal rate below 4.5% was necessary all occurred in environments that had unusually high P/E 10 valuations (above 20). "When stocks markets have more normal valuations (P/E 10 between 12 and 20), Kitces recommended adding 0.5% to the beginning safe withdrawal rate, to 5.0%. When stocks are undervalued (P/E 10 less than 12), the beginning safe withdrawal rate could be bumped 1%, to 5.5%.

It is encouraging that if you are willing to be flexible and disciplined, and you are fortunate to be retiring when stocks are not highly overvalued, you may be able to take higher levels of income from your portfolio than the 4% rule demands. However, before you go rush out and buy that RV or lake house, see some of the reasons you may still want to remain a bit conservative.

People always want to know how much money they need to retire. Alternatively, those that have already pulled the trigger on retirement want to know how much money they can safely spend from their investment portfolio each year. The honest, but unsatisfying answer is (wouldn't you know it)--it depends. It depends on many things, many of which can't be known with much certainty. For instance:

- How long are you going to live?

- How is your portfolio going to be invested over the rest of your life?

- What will your investment returns be, year-by-year, over the rest of your life?

- What will taxes be on your portfolio over the rest of your life?

- Do you wish to leave an inheritance, and if so, how much?

- How sensitive are you to the potential of running out of money in your old age?

You get the picture. Even though we crave a simple answer, life is complicated. And, even though we try our best to create reasonable plans for the future, we are reminded instead just how much is out of our control. In an attempt to create some order out of this chaos, financial planners and economists continue to research and write extensively on the subject of safe (or sustainable) withdrawal rates*.

A safe withdrawal rate is the maximum amount of money, expressed as a percentage of the initial portfolio, which can be withdrawn each year with a very high likelihood that the portfolio would not be completely exhausted within a specified timeframe. The safe withdrawal amount is generally incremented each year to account for inflation in order to maintain a constant purchasing power. The timeframe used is usually one that the individual (or couple) is unlikely to significantly outlive.

The 4% Rule

To illustrate the concept of a safe withdrawal rate let's look what has become known as the 4% rule. First of all it is important to note that the 4% rule is not an absolute like "don't run with scissors" or "time being equal to money". It is more of a rule of thumb, or good practice. You encounter these rules of thumb in many disciplines. Of course, the most famous is "Never get involved in a land war in Asia," but only slightly less well known is this: "Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line!"

The 4% rule (of thumb) is illustrated as follows:

- An investor retires at age 65 with a $1M portfolio.

- This portfolio is invested with a reasonable amount in stocks (e.g. 40-60%) and the remainder in safer bond investments.

- The investor can withdraw $40K (4% of the $1M) in year 1.

- The next year the retiree can withdraw another $40K, plus an inflation adjustment. If inflation was 3%, the withdrawal is adjusted to $41.2K.

- The next year the retiree can withdraw the $41.2K, plus an additional inflation adjustment. If inflation was 5%, the withdrawal becomes $43.26K

- If the future is reasonably similar to the past, the portfolio will be able to sustain these inflation adjusted withdrawals for at least 30 years (until age 95) with a high degree of probability.

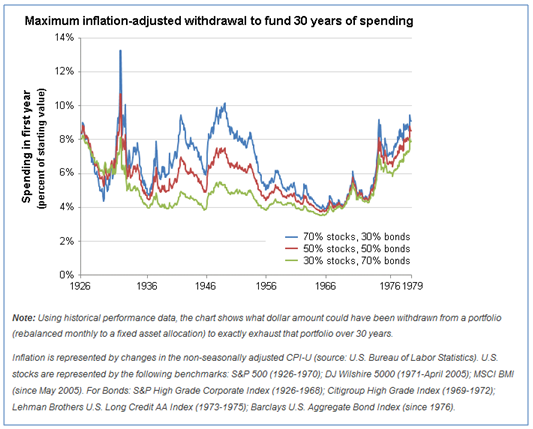

The chart below illustrates the maximum sustainable 30 year withdrawal rates portfolios have supported from 1926 through 1979. (A retiree starting in 1979 would have completed his 30 years of withdrawals in 2009, about when this chart was created.) You will note how retirees starting in the 1960's and early 1970's could only sustain about 4% withdrawals. However, if they had the good fortune to start in the post war years or late 1970's, their portfolios could sustain withdrawals above 6% a year.

Source: Vanguard, "Does the 4% Rule Hold Up", August 2010

Why the difference in sustainable withdrawal rates, depending on the start date? The short answer is folks that face bad markets early in retirement as they start making large withdrawals will only be able to sustain lower withdrawal rates. Those lucky enough to have strong markets early in retirement will likely be able to sustain higher rates of withdrawal. Even if two retirees have identical average portfolio returns over their 30 year retirements, the one who has good years early will do better than the one who faces an early bear market. This is often referred to as sequence risk.

In a world where more of us will be relying on withdrawals from our IRAs and 401K plans, as opposed to guaranteed defined benefit pension plans, we need to understand how to manage our portfolios for long term sustainability. Accordingly, the concept of safe, sustainable withdrawal rates is an important one for retirees and pre-retirees to grasp. Rest assured the 4% rule is not the last word on managing your portfolio in retirement. In follow-on posts, we will discuss why the 4% rule is probably too conservative...or possibly not conservative enough.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------* Some of the early, influential work in the arena of safe withdrawal rates, including the origins of the 4% rule are listed below:

Bengen, William. Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data. Journal of Financial Planning--October, 1994.

Cooley, Philip, Carl Hubbard, and Daniel Walz. Retirement Savings: Choosing a Withdrawal Rate That is Sustainable. AAII Journal--February, 1998.

Ameriks, John, Robert Veres, and Mark Warshawsky. Making Retirement Income Last a Lifetime. Journal of Financial Planning--December, 2001

In Part 1, we covered the first four of ten areas that add significant complexity to retirement planning, making it difficult to do yourself, and a bit dicey to rely on an on-line calculators. Here are the remaining six planning considerations that require flexibility and expertise in the planning process.

5. Retirement spending: On-line calculators often assume that during retirement you are going to spend a certain percentage of your pre-retirement (maybe 70% or 80%) after you retire. While these averages may be OK over a large population, your individual circumstances may be radically different. Some calculators allow you input your own estimate of spending, but usually it is assumed to stay constant in real terms over your entire lifetime. In any case, your spending expectations are a critical assumption and should be carefully considered. How do you deal with "needs" versus "wants"? Are you making reasonable allowances for future medical expenses, including Medicare and supplemental insurance, and potentially long term care insurance? How do you account for the "big trip" every five years, buying the motor home, or helping the grandchildren with college?

6. Social Security: Since Social Security accounts for a sizeable portion of most retirees anticipated income, handling it accurately is critical in projecting retirement income over time. However, Social Security is probably much more complicated than you imagined, and accurately estimating your benefit under different scenarios takes some know-how. And, for those of you concerned about the somewhat shaky state of our nation's finances, you may want to explore how potentially lower Social Security benefits would impact your retirement.

7. Longevity: If we knew exactly how long we were going to live, this whole retirement planning exercise would be much easier. Although dying early is not the preferable outcome for most people, it is much easier to fund a short retirement than a long one. It is the "risk" of a long life, with many years living in retirement that can really stress a financial plan. Unfortunately, many couples plan around an average lifespan, not taking into account the likelihood of at least one living well into the 90's or longer.

8. Long term care: Any retirement plan that does not address the risk of long term care expenses is some manner is incomplete. This may mean choosing to pay for long term care insurance (and including the premiums in your spending projections), explicitly self-insuring by allocating specific assets, or choosing to accept the risks and count on family or the government.

9. Home ownership: For many people their home is their largest single asset, and even if not, it is still a significant part of their net worth. Do you include the value of your home as an asset available to fund retirement expenses down the road? (Remember, you still need to live somewhere.) Do you want the home to be passed down to your heirs, or have it available to tap for long term care expenses? The home is obviously a big consideration that impacts other areas of your planning.

10. Pensions and annuitization: Are you fortunate enough to have an employer provided pension? If so, this needs to be included appropriately in the plan. Will you receive a monthly pension check, or will you get a one-time lump sum payout? Will your pension benefit be indexed to inflation like many government plans, or will it remain fixed and lose purchasing power every year like most corporate pensions? What type of survivorship options will be chosen and how do these impact future income? Even if you don't expect to receive a monthly employer pension check, you have the option to purchase an immediate income annuity--sort of a do-it-yourself pension. Would this strategy help you meet your retirement objectives? Of course, many of these decisions possibly don't need to be made today, but should be considered in the planning process.

Retirement financial projections have many moving parts, many assumptions and difficult computations. Whether you choose to employ a competent financial planner or utilize an on-line calculator, keep your eye on what are the real benefits from the planning exercise. It isn't a fancy financial plan that sits on your shelf, but the big value is in:

- Discussing and setting goals (however tentative) for the future.

- Identifying actions you can take today that help can get you on track to meeting these goals.

- Identifying behavioral changes that you need to make so that you can prosper in life.

- Identifying expectations that need to change in event you are unable or unwilling to make required adjustments.

- Understanding the financial risks you are facing in an uncertain future.

- Having peace of mind that you are adequately prepared for the next phase of life.

- Building the confidence that enables you to make important decisions, take advantage of opportunities and move forward in life.

Those last two points--peace of mind and confidence--are key with so many pre-retirees. Even people who have diligently saved and invested for years in anticipation of retirement want the reassurance and peace of mind that they are adequately prepared. They want confidence they "haven't missed something" and that "they have enough" before they pull-the-trigger and leave their job. When it is time to make these big decisions, the on-line calculators come up short, and it is worth the investment in time, effort, and money to engage a qualified professional.

Just make sure that qualified professional is a fee-only financial planner--one who is a fiduciary and who will put your interests first.

Why would you pay a financial planner to do retirement projections when you can access a plethora of free retirement calculators on the Web? Or, if you're a DIY guy who is handy with Excel--why not do the projections yourself? Or, for that matter, why not take advantage of that "financial advisor" who has offered to do a "free" retirement plan for you?

Go ahead and use the better calculators, or build your own spreadsheets, just to get a top level view of whether you are saving enough or how much you may be able to spend in retirement. But, when real decisions are on the line that will significantly impact your financial future, make the required investment in time and expertise to get the job done right.

Let's take a quick look at ten areas that make retirement planning and projections too complex to be left to most on-line calculators or your home-grown spreadsheet. Here are the first four, and the remaining six will be discussed in Part 2.

1. Inflation: We all know that a dollar today is likely worth considerably less in purchasing power a few years down the road. Making sure inflation is accounted for in a consistent, accurate fashion, is absolutely critical. How many people make the simple logical error of projecting the value of their portfolio at age 65, but fail to also adequately inflate their anticipated spending requirements? Wouldn't it be a shame to wake up and discover that your million dollar portfolio won't support your lifestyle in 2025? (Maybe you should have saved just a bit more.)

2. Investment rates of return: Retirement calculators usually require you to input an assumed investment rate of return. This is obviously a very important assumption, and it's one where everyone pretty much guesses. Granted, even a trained financial planner doesn't have a crystal ball, but he should be able to approach this in a realistic, analytical fashion. For instance, in assembling the retirement projection a competent planner must (or should):

- Make sure nominal rates of return are consistent with the inflation assumptions, resulting in a reasonable real rate of return assumption. (If this one statement doesn't make complete sense to you, you probably don't want to be doing your own retirement projections.) For example, a 6% nominal rate of return may be reasonable with a 3% inflation rate, resulting in a real rate of return of 3%. However, if you are assuming only 1% inflation, this 6% nominal return may be too optimistic. Coupled with a long term 4.5% inflation assumption, it may be too pessimistic.

- Make sure that the return assumptions are consistent with asset allocation decisions. For instance, a 5% real rate of return assumption may make sense with an asset allocation of close to 100% stocks, but makes no sense with an allocation of mostly bonds. Also, you need to consider how your asset allocation will change over time-generally becoming more conservative as you get older.

- Make sure the impact of investment costs is considered adequately. Even if you had perfect foreknowledge of future market returns, that doesn't mean your portfolio will match it after expenses. If you are using mutual funds with expense ratios that average 0.75% per year and you pay an investment advisor another 0.75% per year, then your assumed rate of return should take this 1.5% cost headwind into account.

3. Sequence of investment returns: Although it is important to have realistic real rate of return assumptions, that alone is not enough. As we are all painfully aware, the markets don't deliver their returns in a consistent fashion. Not only is the average of returns important, but the sequence of returns can have a major impact on how well your investment portfolio holds up over retirement. Retirement projections that simply assume a consistent rate of return over the years are much simpler, but can be dangerously optimistic. For example, if you happen to have the misfortune of starting retirement withdrawals in the midst of a bear market like the one just experienced, your portfolio may very well be depleted long before the simplistic model predicted. More complex calculators and financial planning software use Monte Carlo analysis or historical back-testing to gauge how well portfolios will hold up over different conditions. Planning software or calculators that incorporate Monte Carlo analysis are certainly not perfect, but they are helpful and a big step in the right direction.

4. Income taxes: The impact of taxes on your retirement income over the next few decades cannot be ignored, but is a major computational headache. Investment income, retirement accounts, and Social Security all have different tax rules that will influence how much after-tax income you have available to spend. In what order will your retirement assets be tapped, and how does that impact taxation? Do you assume that tax rates will stay similar to today's, or are you concerned that taxes will likely increase?

Before we move on to the remaining retirement planning considerations in Part 2, it's important to step back a bit from the discussion and clarify some important points:

- Planning for your financial future, including retirement, is a very smart thing.

- There are plenty of free or inexpensive resources to help you get started and do some high level planning.

- The whole exercise of planning for decades ahead is very complex and to do this planning well takes time, effort and expertise.

- Although the planning process is extremely valuable, the resulting plan will be wrong--guaranteed.There are just too many assumptions about an unknowable future.

- The key benefit of planning is identifying the necessary actions, attitudes, and behaviors we can modify today to give us the best chance of achieving the desired outcome tomorrow.

Carl Richards provides a helpful analogy from this post on The New York Times' Buck's Blog:

Think of this as the difference between a flight plan and the actual flight. Flight plans are really just the pilot's best guess about things like the weather. No matter how much time the pilot spends planning, things don't always go according to the plan. In fact, I bet they rarely go just the way the pilot planned. There are just too many variables. So while the plan is important, the key to arriving safely is the pilot's ability to make the small and consistent course corrections. It is about the course corrections, not the plan.

For more on the complexity and the value of retirement planning, see Part 2.

Would you rather have $250K in a traditional IRA or $190K in a Roth IRA?

A trick question? Maybe, but if you know much about IRAs, you know the answer isn't obvious. One thing for sure, however, is that a dollar in a Roth IRA is worth more than a dollar in a traditional IRA (or 401k, 403b, or taxable investment account).

There is much to love about the Roth IRA, and at Table Rock Financial Planning we like to see people making the most of the opportunities this flexible, tax-favored investment account offers. Below are a number of key advantages of Roth IRAs and why we recommend them so often.

First, if you are not familiar with Roth IRAs, go here for quick summary and here for a more detailed discussion and comparison with traditional IRAs.

Accessibility of your funds in a Roth IRA

There is often a conflict, especially for younger investors, between establishing a healthy emergency fund (e.g. 3 to 9 months of expenses), saving for major purchases, and contributing to a retirement account. A key feature of the Roth IRA is that the contributions you have made to fund your account are always accessible to you--tax-free and penalty-free. Although a Roth IRA isn't a substitute for a liquid FDIC insured savings account, it is a great back-up. A young investor may choose to keep a somewhat smaller savings account for contingencies, and more aggressively fund a Roth IRA, knowing that in-a-pinch they can access much of the Roth funds (their contributions, not the earnings) without a tax hit. Although the main purpose of IRAs is to put your money aside and let it grow tax free for many years, knowing you can get to the money may allow you juggle multiple financial objectives and to sleep better at night. A few other items related to the accessibility of money within a Roth IRA:

- After a Roth IRA has been established for five years*, an investor can take out up to $10K for the purchase of a first home. This distribution is tax and penalty free, even if some of this money is from earnings, not just contributions. A couple could take out $10K each from their individual accounts, providing up to $20K for a healthy down payment. (If the Roth has not been established for five years, there will be taxes on any earnings, but still no penalty.)

- After a Roth IRA has been established for five years*, investors can access funds to help pay for their children's college. Any portion of the distribution attributable to earnings will be taxed, but there will be no penalty. There are probably better ways to save for college, but sometimes this may be a reasonable option.

- If the account owner dies or becomes disabled ("total and permanent" Social Security definition of disability) the money in a Roth IRA will be available tax-free.

- After you turn age 59.5, all distributions are tax and penalty free as long as the Roth has been established for 5 years*.

- Although your contributions to the Roth IRA are accessible tax-free, different rules apply to funds that have been converted from a traditional IRA.

The ability to save more in tax-favored accounts

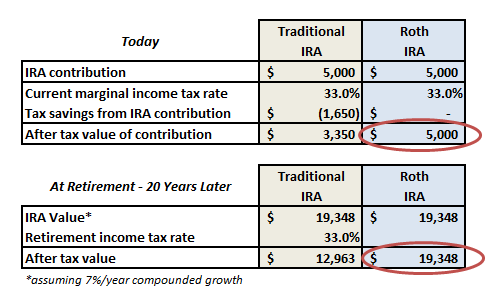

Contributing to a Roth IRA (or Roth 401k or Roth 403b) allows you to effectively save substantially more into tax-favored accounts than with traditional IRAs (or 401k or 403b). To understand this, look at the following simple example:

Note that when you contribute to a Roth IRA you are saving more on an after tax basis than when you save the same amount into a traditional IRA. In order to save the same amount, the person who uses the traditional IRA must also invest the tax savings ($1,650 in this example). However, since the individual is limited to only a $5,000 IRA contribution, the additional $1,650 would need to be invested in a taxable account. The combination of the a traditional IRA and taxable account, even if the taxable account is invested tax efficiently, will generally not be as valuable as the Roth IRA. (The exception to this will be when tax rates are expected to be considerably lower in retirement.)

Tax management in retirement

Many people do precious little thinking on managing their current tax situation, let alone consider how they will minimize their taxes in retirement. If all of your retirement accounts are traditional IRAs (including roll-overs from employer retirement plans such as 401ks), all of your distributions will be fully taxable. If you need to withdraw additional money in a particular year, you will increase your taxable income and probably your tax liability. However, if you have the option of tapping funds in a Roth IRA instead, you can take a larger distribution without negatively impacting your tax situation. Some other tax considerations to note:

- Additional traditional IRA distributions may move you into a higher tax bracket, and possibly cause a higher percentage of your Social Security benefits to be taxed. This interaction with Social Security, and possibly even Medicare, can make the marginal tax impact of an additional distribution much higher than you would normally assume.

- Also, higher income associated with higher taxable distributions cause tax deductibility thresholds (e.g. the 7.5% of AGI threshold to deduct medical expenses) to be higher--in effect lowering your deductions and increasing taxes in another way.

- Unlike the Roth IRA, it is important to note that traditional IRAs are subject to required minimum distributions (RMDs). Even if you don't need the money from your traditional IRA, you will be required to take distributions and pay taxes after you turn age 70.5. These RMDs are a bit of a hassle to keep track of, and it is possible to make mistakes and incur significant penalties.

The Roth IRA also gives the investor an advantage often referred to as tax-diversification. Are you concerned that income tax rate may go up in the future? Many people are, and paying taxes today effectively locks in the rate that you pay--allowing you to shield yourself from the risk of higher future rates. (It is important to note that if you expect lower income in the future, you may still pay a lower income tax rate in retirement--even if Congress raises taxes.

These aren't the only things to like about the Roth IRA. The Roth is more straight-forward, easier to understand, and easier to manage long-term than traditional IRAs. And, if you plan on passing along IRA assets to your loved ones, it is to their advantage to inherit a Roth IRA, where the taxes have already paid. If you aren't taking full advantage of the opportunity Roth IRAs provide, it will pay to take a closer look.

For information on converting traditional IRA assets to a Roth IRA, look here.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*This five year period (or five year rule for withdrawals) is defined as beginning with the first taxable year for which the account holder has a Roth IRA contribution of any kind. There is a different five year rule that pertains to Roth conversions, and the difference is explained in this article.

Although many economists and financial planners encourage people to wait until full retirement age or later to start taking Social Security retirement benefits, there are circumstances where it is financially prudent to apply for benefits early. In Part 3, some of these situations are discussed, and two more opportunities for taking benefits early are summarized below.

Effective use of the spousal benefit: Imagine the situation of a couple where both plan on maximizing their benefits by waiting until age 70. (They had been reading financial planning blogs, and thought this sounded smart.) They can accomplish this goal of maximizing their long term benefits, and take some benefits earlier, too! Here's how. Suppose the husband reaches his FRA (full retirement age) first, and he "claims and suspends" as discussed in Part 3. When his wife reaches her FRA, she is able to apply for spousal benefits (only spousal benefits, not benefits on her own record*) and immediately start receiving 50% of her husband's PIA. At age 70 the husband claims his enhanced benefit, and when the wife turns 70 she switches from the spousal benefit to her own higher benefit.

If a lower earning wife had chosen to take her benefit at age 62 (as discussed in Part 3) a related strategy could be employed. Since she has claimed her benefit, her husband is able to claim a spousal benefit off of her record. As long a he waits until his FRA, he can claim this spousal benefit (50% of his wife's PIA). He can receive those spousal benefits for the three or four years it takes for him to maximize his own benefit at age 70, at which time he switches to a benefit based on his own record.

Claim early and pay it back: If you aren't convinced that Social Security is not just more complex than you ever imagined, but pretty darn wacky also, check this out. Believe it or not, the SSA allows recipients to "withdraw their application" for benefits, giving individuals an opportunity for a "do-over". All individuals have to do is file Social Security Form 521, and repay all the benefits previously received on their earning record-with no interest or penalty. The individual can then reapply for higher benefits, as if they never received the early payments.

If you have not connected the dots--this amounts to an interest free loan from your fellow citizens. You can take benefits at age 62, invest them, and eight years later pay back the benefits you have received. At age 70 you restart taking your benefit, which has been enhanced with delayed retirement credits. Wow--I'm not making this up. Here is an article, and another, that discuss this option. Of course, just like a lot of things--just because you can doesn't mean you should do it. Here are some things to consider:

- To state the obvious, you better be disciplined enough to have the money put aside to pull this maneuver off.

- This may be a great strategy for a disciplined single person. After taking benefits at age 62 and banking the proceeds, the person can reassess the situation at age 70. If they think they are reasonably likely to live until life expectancy or beyond, they withdraw their application, repay, and reapply for the higher benefit. If their health is dodgy, and they are unlikely to make until life expectancy, than it makes sense not to withdraw and repay.

- For married couples, it is not so simple. As has been previously stated, it is usually wise for the higher wage earner to wait until about age 70 to take benefits, in order to maximize survivor benefits. If the higher wage earner takes benefits at age 62, with the intention of taking the "do-over" at age 70, the couple takes a significant risk. If the higher wage earner happens to die prior to the "do-over", the surviving spouse is left with a significantly reduced survivor benefit. By going for the interest free loan, the couple really screws up.

- Income taxes will likely have been paid on some of the benefits you have received but are paying back. However, you can recover these tax payments in a couple of different ways. (See IRS Publication 915, page 15.) To fully recover your taxes, you will likely have to refigure your taxes for each year you received benefits you are repaying. If you are planning to utililize this strategy, it will be easier if you figure your income taxes with and without your Social Security benefits as you go along.

- If this ability to take an interest free loan from Social Security sounds stupid to you, someone in Congress may eventually catch on. You have to think that Congress will be doing some significant tweaking of the Social Security system in the next few years--right after they fix the whole BCS mess. In the meantime, if you decide to take advantage of this "do-over" provision, make sure you are paying attention. While the SSA or Congress are "under the hood", fooling around with the retirement age, payroll taxes, COLA provisions, etc., they may take the time to fix this absurdity. Even if the provision isn't removed entirely, you would have to think it would be changed to so as not to be so advantageous a loophole.

The decision of when to start Social Security benefits, and how to coordinate benefits between spouses, is one of the biggest financial issues many folks face today. Unfortunately, many make these choices without adequate understanding or guidance. It pays to do your homework, or seek out competent financial planning advice. The complexity of the Social Security system is truly amazing, but provides some interesting opportunities for the knowledgeable.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

*Prior to reaching full retirement age (FRA) when a married person applies for benefits it is assumed that the person is applying for both a benefit based on their own record and a spousal benefit. (It is subject to something called a "deemed filing" provision.) After reaching FRA, however, the rules change and a person can select whether they receive a spousal benefit or their own earned benefit.

In Part 2 of this series the advantages of waiting to claim Social Security benefits was examined. (Part 1 explained the basics about how the decision of when to take one's benefit affects the size of the benefit.) There are two key takeaways from this discussion. First, don't rush to take your benefits early-it may be in your and your spouse's best interest to wait. Second, Social Security retirement benefits are a complex topic, and making the most of them takes considerable understanding.