In Part 1, the complex set of rules surrounding Social Security survivor benefits was explored. Survivor benefits can be crucial in providing an economic safety net for families that lose a provider’s income. In this post, we will look at some tips for making the most of the survivor benefits potentially available to you. But first, it is important to clarify exactly what a person must do for their family to be eligible to receive Social Security survivor benefits.

Worker eligibility

- A worker generally becomes eligible for Social Security retirement benefits after earning 40 work credits–or 10 full years. Work credits are earned by working in “covered” employment (including self-employment) where Social Security taxes are paid.

- However, the amount of credits a worker must have accumulated for his dependents to receive survivor benefits depends on the age of the worker at death. The younger a worker is, the fewer credits are necessary for the family to be eligible for survivor benefits. For example, a worker under age 28 would only need 6 work credits, at age 34 it is 12 credits, and at 46 it is 24 credits. If the worker dies at age 62, 40 work credits are required–the same as for retirement benefits.

- Finally, there is a special rule allowing a deceased worker’s children and spouse caring for children to receive benefits even if the worker didn’t have the number of required credits. In this situation with dependent children, benefits are available as long as the worker simply had accumulated 6 credits (1.5 years of work) in the three years prior to death.

Planning tips

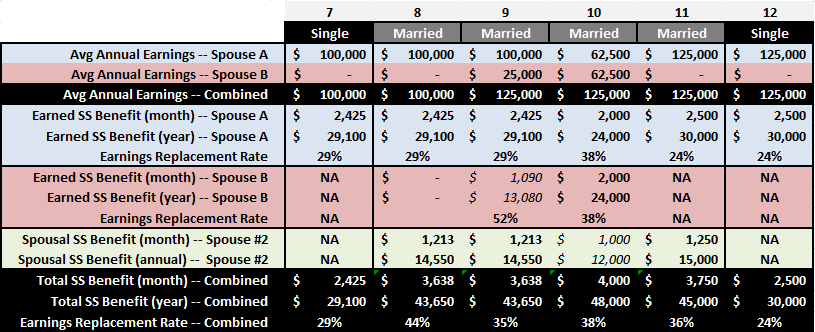

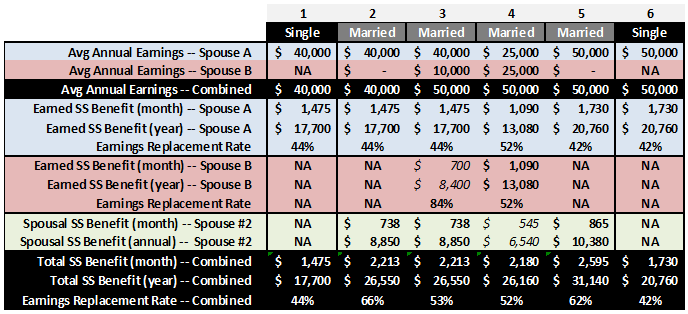

- While still alive, have the highest earner maximize their benefit. Although the majority of people choose to start their retirement benefits early, with married couples it is often wise to maximize the higher of the two benefits. This entails having the spouse with the highest earned benefit wait until 70, gaining delayed retirement credits. This maximized benefit will then be available across both spouses’ lifetimes. This is the most cost effective way to secure a healthy inflation adjusted lifetime income stream that will protect a couple from longevity risk. This strategy is most compelling when the higher earner is the older spouse, and has a shorter expected lifespan (often the male).

- Coordinate survivor and personal benefits wisely. If you are eligible for both a personal benefit off of your own work record and a survivor benefit off of a deceased spouse’s work record, you have an important opportunity maximize the long term value of the combined Social Security benefit stream. The general rule is to maximize the larger of the two benefits by waiting to start it at the most opportune time. Compare what your personal benefit will be if you wait until age 70 (maximized with delayed retirement credits) with the survivor benefit at your full retirement age (FRA—after which it will not grow). If your maximized personal benefit is the highest, delay taking it until age 70. In the meantime, start taking the survivor benefit as early as age 60 (usually as soon as you stop working), then switching to your own benefit at 70. If the survivor benefit at FRA will be the highest amount available to you, wait until FRA to start it. In the meantime, you can start your personal benefit at age 62. Using this strategy, you benefit from the largest possible retirement benefit for the longest possible time.

- Your survivor benefit may not be maximized at your FRA. If your deceased spouse started his or her benefit prior to their FRA (and many, many do), then are situations when it will not make sense to wait until FRA to start. (Remember the widow(er)’s limit provision mentioned in Part 1.) For example, if your spouse filed early enough, your benefit may never be larger than 82.5% of their PIA. Your survivor benefit may be maximized at this 82.5% a few years earlier than your FRA, and it may not make sense to wait any longer to start taking it. This is complex, so if your deceased spouse started taking retirement benefits early and you have yet to reach your FRA, contact the SSA and have them calculate when your survivor benefit will be maximized.

- Be mindful of the earnings test. In the years prior to hitting your FRA survivor benefits are subject to the earnings test. If you are still working, it may be counter-productive to start taking survivor benefits if you are going to lose $1 of benefits for every $2 you earn over the limit (in 2012 it is $14,640). Depending on the situation, it may, or may not, make sense to start receiving benefits if you are still working. It may be wise to delay starting and let your benefit get larger.

- Get married. Survivor benefits are available to married couples, not to those couples who have chosen not to tie-the-knot. Your decision not to encumber your relationship with the bonds of marriage may prove to be an expensive one, when you consider lost survivor and spousal benefits. Most unmarried couples (at least the ones I talk to) are oblivious to the availability and value of survivor and spousal Social Security benefits.

- Hold it…maybe you don’t want to get married until age 60. Make that remarried. Remarriage prior to age 60 will make you ineligible for survivor benefits off of a deceased spouse’s record. (If that remarriage ends, you will again be eligible for the survivor benefits.) If you are contemplating remarriage and you are getting close to age 60, it might just be worth waiting a few months…or years. It is possible that these survivor benefits may be more valuable than your personal benefit, or any spousal benefits available off of a new spouse’s record. The survivor benefits are also available earlier (age 60) than your personal or spousal benefits (age 62). Don’t underestimate the potential value of wisely coordinating a survivor benefit with your personal benefit.

- Keep track of your ex-spouse. If you were divorced after being married for at least 10 years, you may be eligible for a survivor benefit off of your ex-spouse’s work record, if he or she passes away. Your ex-spouse is dead, and money now starts appearing in your checking account! This may sound too good to be true, but hey, this is America. Again, remarriage prior to age 60 will make you ineligible (unless that marriage ends, also). Don’t count on the SSA to magically find you, though. You will need to contact them and prove your eligibility for a survivor benefit.

- Survivor benefits are listed on your Social Security statement. Although these are not mailed out annually like they used to be, you can always get an updated statement here. Your statement tells you what your spouse and children would be eligible for if you were to die this year.

This long two part series on Social Security survivor benefits can be summed up neatly with just three key observations. First, Social Security is complicated—more complicated than you ever imagined. Second, what you don’t know about Social Security can cost you a considerable amount of money in forgone benefits. Third, obtain skilled counsel before making your Social Security filing decisions. Seek out a fee-only financial planner who has developed expertise in this critical area before it is too late.